[OTHER ARTICLES]

|

||

| Boukman wasn't named Zamba | ||

Author : Rodney Salnave

Function : Dougan (Scribe)

Date : September 24, 2016

Function : Dougan (Scribe)

Date : September 24, 2016

(Updated : July 28, 2019)

Proponents

of the muslim farce present the name "Boukman" as one-of-a-kind. This

custom-made name was supposedly allocated to Boukman by a Jamaican

settler who caught him reading a koran (holy book of muslims). Following

this, as Boukman was supposed to always carry that koran, the English

words "Book" and "Man", were then combined to describe him as a

so-called "Man of the Book", as in a muslim priest.

The worst part of this is that such a far-fetched fabrication that is not supported by any historical evidence, is believed even by educated people. To date, nobody can locate that plantation in Jamaica to which Boukman belonged, nor the name of the English planter who would have nickmaned him "Book-Man". Unfortunately, when it comes to subjects specific to black peoples, precision and historical evidence suddenly become insignificant. The truth is then whatever one wishes it to be.

This article will trace the origin of the falsehood stating that Boukman owned a book, as well as the genesis of the claim that he hailed from Jamaica. We will prove this through 4 points.

The worst part of this is that such a far-fetched fabrication that is not supported by any historical evidence, is believed even by educated people. To date, nobody can locate that plantation in Jamaica to which Boukman belonged, nor the name of the English planter who would have nickmaned him "Book-Man". Unfortunately, when it comes to subjects specific to black peoples, precision and historical evidence suddenly become insignificant. The truth is then whatever one wishes it to be.

This article will trace the origin of the falsehood stating that Boukman owned a book, as well as the genesis of the claim that he hailed from Jamaica. We will prove this through 4 points.

1- "Bouc" and "Bouque" are French words :

First of all, the word "bouc" is part of the French language lexicon. It is the common designation of the male goat* :

"Bouc. nm1. (zoologie) mâle de la chèvre" (1)

Translation :

Likewise, they call a male goat "bouk" in Haitian Creole. In addition, in French, we find "bouque", which is the third person singular form of the verb "bouquer" :

"Bouc. nm1. (zoology) male goat"

Likewise, they call a male goat "bouk" in Haitian Creole. In addition, in French, we find "bouque", which is the third person singular form of the verb "bouquer" :

"Bouquer, un cheval qui bouque éprouve une fourbature instantanée qui l'empêche de marcher. C'est une extravasation de la synovie qui n'a pas de suite fâcheuse à Saint-Domingue. Le climat empêche l'endurcissement, et peu de jours suffisent pour rendre au cheval bouqué la lubréfication de ses membres." (2)

Translation :

"Bouquer, a riding horse that "bouque" experiences an instantaneous whipping that prevents it from walking. It is an extravasation of the synovia that doesn't have an unfortunate outcome in Saint Domingue. The climate prevents hardening, and it takes only a few days to give the clogged up "bouqué" horse back the lubrication of its limbs."The verb "bouquer", commonly used in Saint Domingue, is even retained in Haitian Creole. It refers to being exhausted, tired, literally and figuratively. (3) But, we will insist here more on the French naval word "bouque" and its derivatives :

"BOUQUE (Mar.): Mot dont on faisait usage autrefois en Amérique, pour désigner un passage, un canal ou un détroit." (4)

Translation :

"BOUQUE (Maritime.): Word used in the Americas to designate a narrow path, a channel, a straight."

"HIST. XVe s. Et vindrent à passer devant une bonne ville qui sied à l'entrée de la bouque de la mer majeure, Bouciq. I, ch 32.Translation :

XVIe s. Le Tybre croist par les vents austraux qui, soufflans droict en sa bouque près Hostie, suspendent son cours, RAB. Sciomachie." (5)

"HIST. 15th century. And they came to pass by a good city located at the foot of the "bouque" of the major sea, Bouciq. I, ch 32.16th century. The Tybre [Italian river] grows stronger by the southern winds that, blow directly in its "bouque" near Hostie, pausing its flow, RAB. Sciomachie."

Fort la Bouque

"Le fort la Bouque est sur la pointe est de la baie du fort Dauphin [Fort Liberté actuel], dont la beauté avait donné lieu au premier nom qu'elle reçut des Espagnols et qui devint celui de toute cette partie de l'île.(…)

"Fort la Bouque, mot francisé de l'espagnol Boca, qui signifie entrée, bouche, et dont une prononciation vicieuse fait déjà le fort la Boucle." (6)

Translation :

"Fort la Bouque is located on the Eastern edge of the bay of Fort Dauphin [currently Fort Liberté], whose beauty had caused it to be the first to receive a name by the Spaniards, and that became that of all of this part of the island.(...)Fort la Bouque, frenchified word from the spanish Boca, that means entry, mouth, and that a faulty pronounciation had previously rendered Fort la Boucle."

On July 7, 1768, 23 years prior to Bois Caïman, this ad issued from the Saint-Marc prison, mentions 2 captives (slaves) living in "La Bouc", Fort-Dauphin (current Fort-Liberté) :

Débouquement

"Le 7, deux Nègres Congo, l'un nommé Jacquet, étampé sur le sein droit, autant qu'on a pu le distinguer, MACA, âgé de 25 à 26 ans, taille de 5 pieds 4 pouces, ayant des marques incisives de son Pays sur le front et sur les deux tempes, l'autre nommé Martin, étampé sur le sein droit MOCA, et sur le gauche ALC, du même âge et de même taille, se disant appartenir à M. Chales, Habitant à la Bouc, Quartier du Fort-Dauphin." (7)Translation :

"On the 7th, two Congo Negroes, one named Jacquet, stamped on the right breast, as far as we could distinguish it, MACA, 25 to 26 of age, height of 5 feet 4 inches, having incisive marks of his Country on the forehead and on both temples, the other named Martin, stamped on the right breast MOCA, and on the left ALC, of the same age and size, claiming to belong to Mr. Chales, Residing in la Bouc, Fort Dauphin area."

Débouquement

"On entend par le mot de Débouquement, un Passage étroit entre des terres, dans lequel il faut faire route pour sortir d'un Parage, ou quitter une Côte. Ce mot vient des Espagnols, qui ayant navigué les premiers dans ces cantons, nommèrent ces Passages et ces Entrées étroites Bocca, en français Bouches, dont les Marins ont fait le mot de Débouquement, pour dire sortir par une Bouche ou Passage étroit. On dit aussì embouquer pour entrer : mais ces termes ne sont en usage que parmi les Marins." (8)Translation :

"By the word Débouquement, we mean, a narrow passage between the land in which you have to drive out a trimming or leave a Coast. This word comes from the Spanish, who were the first to sail these cantons, and who named these passages and narrow entries Bocca, Bouches in French, the sailors transformed it into Débouquement, to say out by mouth or narrow passage. They also say enbouquer to enter, but these terms are in use only amongst the sailors."

"Vue du Débouquement de St.-Domingue", Moreau de St.-Méry, 1875.

Bouqueton

On July 29, 1768, 23 years before Bois Caïman, this ad coming out the the Fort Dauphin prison deals with Pélagie, a captive (slave) woman of Ibo ancestry, who is owned by Marguerite Bouqueton, a free blackwoman :

"Le 29, une Négresse Ibo, nommée Pelagie, étampée sur le sein droit LAF, se disant appartenir à la nommée Marguerite Bouqueton, n.l. demeurant à Ouanaminthe." (9)

Translation :

"On the 29th, an Ibo Negress, named Pelagie, stamped on the right breast LAF, claiming to belong to the said Marguerite Bouqueton, n.l. [free blackwoman] living in Ouanaminthe."

In short, we clearly see that the words "Bouc", "Bouque", "Débouquement" as well as "Bouqueton" are part of the French lexicon used in the Saint Domingue colony. This debunks the pathetic claim that the sound "Bouque" could only come from the English word "Book".

2- Here is the origin of the "Jamaican Boukman" lie :

(1785)

In 1785 - just six years before Bois Caiman - de Bellecombe, then Governor General of Saint Domingue, capitulated to a maroon band who took refuge in the mountains nearby Jacmel (Southern Saint Domingue). (10)

(1801)

Pierre François Page, a settler serving as Commissioner of Saint Domingue, wrote on the 125 maroons whose freedom reminded him of a similar act of the British in Jamaica in 1733 :

"En 1733, l'Angleterre fut forcée de reconnaître l'indépendance de quelques Nègres révoltés à la Jamaïque ; et M. de Bellecombe, gouverneur à Saint-Domingue, fut obligé de faire, en 1785, une capitulation semblable avec 125 Nègres marrons." (11)Translation :

"In 1733, Britain was forced to recognize the independence of some revolted Negroes in Jamaica ; and M. de Bellecombe, Governor of Saint Domingue, was obliged to make in 1785 a similar capitulation to 125 Maroons."

(1805)

1 year after the independence of Haiti, 14 years after Bois Caiman, Phillipe Lattre, an abolitionist, was praising Boukman, when he became the first to deform "Boukman" into "Bouk-man". Similarly, he was the first to think that the name Boukman can be broken down in the English language. That's what lead him to say that Boukman was English, and that he was among the 125 maroons freed by Bellecombe. Shamelessly, the author pretended that these 125 maroons came from Jamaica and not locally, in nearby Jacmel :

"Le premier Spartacus de Saint-Domingue, était un nègre de nom anglais, nommé Bouk-man, qui n'a pas été connu appartenir à la colonie. Il était un envoyé des anglais, ou l'un des chefs des cent vingt-cinq nègres marons, que le gouverneur-général de Bellecombe avait reconnu indépendans." (12)Translation :

"The first Spartacus of Saint Domingue, was an English-named negro called Bouk-man, who was not known to belong to the colony. He was sent by the English, or one of the leaders of one hundred twenty five maroon negroes, the Governor-General de Bellecombe had recognized as free."

Moreover, no one in the colony has never argued that Boukman hailed from Jamaica, or even that he spoke English. None who knew him, no runaway ad, nor official colonial paper, ever mentioned such origin. Nothing hints that Boukman came from elsewhere. It was only post the independence of Haiti that Phillipe Lattre, well at ease in France, imagined an English filiation to the Boukman name. Obviously, he was delirious.

And to erase all doubts concerning Boukman's origin, we must point out that he, unlike what Phillipe Lattre stated, was in fact known to the colony. In 1785, at the time of the freedom of the 125 Southern maroons, according to town delegate Leclerc, (13) Boukman belonged to his family, at the Turpin Estate of Limbé (North province) from where, 4 years later, in 1789, he was sold to the Clément Estate of l'Accul (North) :

"We have a few other pieces of informations about Boukman. Leclerc, the procureur-syndic of the Limbé town council at the time of the insurrection and later, from October 1792 to June 1793, the governement delegate to the Le Cap law court, drew up some notes that inform us that Bookman had been a slave on his familiy's plantation and that he was considered a "bad slave." He ran away but did not go far; he came back to the plantation at night to get food. After being discovered one night by Leclerc's brother, he was shot and wounded, then sold. This is how he ended up on the Clément plantation in Acul, a parish next to Limbé. He cannot have been considered all that "bad" a slave, since he was employed in the trusted position of coachman." (14)

(1808)

Henri Baptiste Grégoire (Abbé Grégoire), who was a renowned abolitionist author, took over the story of the 125 maroons, but from the Pierre François Page text published in 1801-1802. He spoke of the 125 maroons from the vicinity of Jacmel, and not Jamaica :

Translation :"Les Nègres marrons de Jacmel ont, durant près d'un siècle, épouvanté Saint-Domingue. Le plus impérieux des gouverneurs, Bellecombe, fut obligé, en 1785, de capituler avec eux; ils n'étaient cependant que cent vingt-cinq hommes de la partie française, et cinq de partie espagnole." (15)

"The Jacmel Maroons have, for nearly a century, terrified Saint Domingue. The most compelling of Governors, Bellecombe, was compelled in 1785 to surrender to them. They were, however, only one hundred twenty five men of the French side, and five from the Spanish part."

(1826)

Translation :

The author

Placide Justin, without citing any source, adopted Phillipe Lattre's

hypothesis by presenting Boukman as a "creole from

English islands" :

"Ce jour, à dix heures du soir, les noirs de l'habitation Turpin, sous la conduite du nègre Boukmann, créole des îles anglaises, entraînant avec eux les esclaves des habitations voisines, se répandent dans toute la dépendance du Cap..." (16)

"At ten o'clock in the evening, the blacks of the Turpin estate, led by the negro Boukmann, creole from the English islands, dragging with them the slaves of the neighboring dwellings, spread themselves throughout Le Cap..."

That same year, Victor Hugo, a young author, rewrote his first novel devoted to the Saint Domingue revolution. It is based on the Phillipe Lattre falsification that Boukman was an old maroon from Jamaica that de Bellecombe (Governor of Saint Domingue, not Jamaica) have released. But Victor Hugo took where Phillipe Lattre left off. Writing a novel, and not a history book, he made full use of the artistic freedom to which he is entitled. Thus, he brought the Phillipe Lattre audacity further by inventing that Boukman originated from Jamaica's Blue Mountain region :

"Bouckmann, chef des cent vingt noirs de la Montagne Bleue à la Jamaïque, reconnus indépendants par le gouverneur-général de Belle-Combe..." (17)

"Bouckmann, head of one hundred and twenty blacks of the Blue Mountains in Jamaica, recognized independent by the Governor General of Belle Combe..."

(1831)

"Jean-François, dernier domestique de M. Papillon, s'était placé au Dondon. Boukman, nègre des montagnes bleues de la Jamaïque, était à la soufrière de l'Acul." (18)Translation :

"Jean-François, last servant of M. Papillon, camped at Dondon. Boukman, negro of Jamaica's Blue Mountains, was at the outskirts of l'Acul."

(1850)

Saint-Remy, a Haitian historian, joined the lying about Boukman club. However, he did not have knowledge of the Mollien work that was unpublished. The Victor Hugo novel, by essenc non-scientific innature, sserved him, nevertheless as source. A clue lies in his spelling of "Bouckman" that is close to "Bouckmann" in Victor Hugo's novel :

Translation :"Le chef principal avait nom Bouckman, africain primitivement vendu à la Jamaïque, d'où il fut porté à Saint-Domingue; il appartenait à l'habitation Clément. Cet homme, doué d'une force herculéenne, ne concevait pas ce que c'était que le danger; il marchait au combat avec l'enthousiasme d'un fanatique, semant la flamme de l'incendie et couvrant sa route de cadavres." (19)

"The main leader was called Bouckman, African originally sold to Jamaica, from where he was brought to Saint-Domingue. He belonged to the Clement estate. This man, endowed with Herculean strength, had no conception of danger; he walked into battle with the enthusiasm of a fanatic, spreading the flame of fire and covering his path with corpses."

(1925)

Finally, in 1925, it was game over. The stampede had begun. Dorsainvil, in cohort with the Frères de l'Instruction Chrétienne, repeated the Jamaican Boukman urban legend without the required checks. Ever since, Haitian schoolchildren are forced to recite this falsehood :

"Boukman était né à la Jamaïque; c'était un houngan, c'est-à-dire un prêtre du vaudou; il était de haute taille et fort comme un géant; il exerçait une influence extraordinaire sur les autres esclaves." (20)Translation :

"Boukman was born in Jamaica, he was a houngan, that is to say, a priest of vodou; he was tall and strong like a giant; he exerted an extraordinary influence on the other slaves."

Here is how a historical event such as the Governor General de Bellecombe releasing 125 untamable maroons nearby Jacmel (South of Saint Domingue, Haiti), was converted into a Jamaican lie that revisionists seized to advocate the islamization of Boukman.

In these two previous excerpts, one must also take notice of "endowed with Herculean strength," or "tall and strong as a giant" that are racist and unfounded expressions continually attributed to Boukman and many other Haitian revolutionaries (21-22), including Cécile Fatiman (23) to suggest that physical dominance, not intellect, is the sought aftter requirement of leadership among the Blacks (depicted as wild and intellectually impoverished). But of course, the size of Boukman, nor that of Macandal, has never attracted eyewitnesses' attention. Moreover, Henry Christophe, the Haitian revolution leader, was the only one blessed with an imposing physique. (24) And rare were the band leaders - aside from Alaou (25) - that possessed an extravagant frame. Unfortunately, Haitian historians have no issue with passing on degrading colonial stereotypes to the people they claim wanting to educate for a better future.

The sole link between Boukman and the Blue Mountains

Moreover, it was due to the warlike reputation of the black Jamaicans from Blue Mountains that Victor Hugo, in his novel Bug-Jargal (1826), had placed his Boukman character as native of Blue Mountains. But the novelist would never have imagined that historians would have taken as historical fact, what he intended as pure fiction.

The sole link between Boukman and the Blue Mountains

Finally, in September 1791, as Boukman was battling the settlers, Saint Domingue's colonial assembly requested a Jamaican loan in order to financially support the Northern planters coping with severe losts. In addition to money, the French followed Jamaica's representative Bryan Edwards' proposal, by officially requesting slaves troops from the Blue Mountains that are known for submiting rebel slaves :

"Le présent arrêté sera présenté à M. le Lieutenant au gouvernement général et représentant de Sa Majesté dans la colonie, pour avoir son approbation, et être par lui adressé au lord Effingham, avec pièce de le communiquer à l'assemblée de la Jamaïque.

L'un des membres a observé, que les ateliers étant toujours en révolte, et n'ayant point de troupes de ligne à espérer, il croyait qu'il était de la sagesse de l'assemblée de profiter de l'ouverture qu'avait fait M. Edouards, que peut-être le gouverneur de la Jamaïque consentirait à nous envoyer les Nègres de la montagne Bleue, seule troupe employée dans cette île pour soumettre les esclaves rebelles.

Cette motion appuyée, l'assemblée arrête que son président s'entendra avec M. le Lieutenant au gouvernement général, pour demander au gouverneur de la Jamaïque le Nègres de la montagne Bleue." (26)

Translation :

Ultimately, hostile to the French, British Jamaica did not provide Saint Domingue with black troops from Blue Mountains ; although French judge Garran-Coulon believes Jamaica was open to the idea. (27) But the irony of the story is that not only Boukman wasn't from Jamaica's Blue Mountains, he was potentially the enemy of those Jamaican Blacks that allied with settlers against freedom seeking Blacks."This order shall be submitted to Mr. Lieutenant to the Governor and His Majesty's representative in the colony, for its approval, and by him addressed to Lord Effingham, with room to communicate it to the Jamaican Assembly.

One member noted that the workshops being still in revolt, and having no regular troops to hope, he believed it was wise of the assembly to take advantage of the opening thad Mr. Edwards did, that perhaps Jamaica's governor would agree to send us Negroes from Blue mountain, the sole troop used in this island to subject rebellious slaves.

This motion supported, the assembly rules that its president will agree with Mr. Lieutenant General Government, for asking Jamaica's governor the negroes from the Blue Mountain."

Moreover, it was due to the warlike reputation of the black Jamaicans from Blue Mountains that Victor Hugo, in his novel Bug-Jargal (1826), had placed his Boukman character as native of Blue Mountains. But the novelist would never have imagined that historians would have taken as historical fact, what he intended as pure fiction.

3- Here's a list of 12 people named Boukman in the colony :

Boukman #1 : January 26, 1750, Bouqueman, is a Black guy from Le Cap who was involved in the abduction of a young woman :

"Demeurant au Cap, où elle a resté trois jours, que de là elle fut chez M. Delarue, ensuite chez Mme Beauval, à la case du nommé Bouqueman, où elle aurait été arrêtée marrone quelques temps auparavant, et de là, conduite par ledit Nègre à son père sur l'habitation Carbon au Bois de Lance, où elle a presque toujours resté depuis, et ce, dans la vue de forcer ledit frère Lavaud de la vendre." (28)Translation :

"Residing in Le Cap, where she stayed three days, from there she was taken to Mr. Delarue's residence, then to Madame Beauval's, at the shed belonging to the named Bouqueman, where she was arrested as a mid-term maroon, and from there, led by the said Negro [Bouqueman] to her father at the Carbon estate in Bois Lance, where since, she almost always remains, and this, in order to force the so-called Lavaud brother to sell her."

Boukman #2 : December 15, 1757, funeral of Pierre Boukman, a French settler in Port-au-Prince :

“Enterrement de Pierre Boukman - Aujourd'hui quinzième décembre mil sept cent cinquante et sept a été inhumé dans le cimetière de cette paroisse le corps de Pierre Boukman natif de Luré en Flandre. Agé de trente six ans, décédé à l'hôpital, muni du sacrement de pénitence…” (29)Translation :

"Burial of Pierre Boukman - Today December 15, 1757, was buried in the cemetery of this parish [Port-au-Prince, West province] the body of Pierre Boukman, native of Lure in Flandre [France]. Aged 36, died in hospital, was provided the sacrament of penance..."

Boukman #3, 4 : 1761, in the inventory of "la Sucrerie Saint-Michel" located at Pointe Icaque (North), there were 2 White women named Bouquemen :

"Il est intéressant de trouver deux femmes qui s’appellent Bouquemen, nom du premier chef des révoltés de 1791. Bouquemen créole « vieille » et Cécile Bouquemen Guillebedau, se trouvent côte à côte sur la liste. Elles sont peut-être mère et fille." (30)Translation :

"It is interesting to find two women called Bouquemen, name of the first leader of the rebels of 1791." Bouquemen Creole « old lady » and Cécile Bouquemen Guillebedau, lie side by side on the list. They may be mother and daughter."

Boukman #5 : February 10, 1776, this "Bouquemant" is perhaps a Creole "mint" salesman?

"Au Cap, le 4 de ce mois, Bouquemant, créole, étampé illisiblement, lequel a dit appartenir à M. Le Conte, Procureur de l’Habitation Portelance" (31)Translation :

"In Le Cap, on the 4th of this month, Bouquemant, Creole, stamped illegibly, said to belong to Mr. Le Conte, Prosecutor of Portelance Estate."

Boukman #6 : October 5, 1779, "Bouqueman" is a dangerous hunter from the North-East aged 40-42:

"Trois Nègres nommés Bouqueman, chasseur ; Jean-Jacques, créole, cocher, sans étampe, & David, étampé X, Nègre de Guinée, sont partis marons de l'Habitation de M. Cailleau aîné & de Mde veuve Dorlic, à Maribaroux [Nord-Est] : les deux premiers, âgés de 40 à 42 ans, sont deux sujets des plus dangereux qu'il est important d'arrêter, l'un taille de 5 pieds 3 pouces, figure ronde, les yeux petits & d'un regard farouche ; le cocher, taille de 5 pieds 4 pouces, les yeux enfoncés, les narines ouvertes, grande bouche, lui manquant des dents de devant, les jambes cambrées & jetant de côté de la gauche en marchant, ce dernier évadé avec un nabot, une chaîne & des serre-pouces. Ceux qui les reconnaîtront, sont priés de les faire arrêter & transférer dans les cachots les plus voisins & avec le plus de sureté possible, & d'en donner avis au Sieur Dorlic, à Maribaroux." (32)Translation :

"Three Negroes named Bouqueman, hunter ; Jean-Jacques, Creole, coachman, without stamp, & David, stamped X Negro from Guinea, went marooned off the Mr. Cailleau aîné & widow Mde Dorlic Estate at Maribaroux [North-East]: the first two, aged 40 to 42, are two of the most dangerous subjects it is important to stop, one sized 5 foot 3 inches, round face, small eyes & a wild look; the coachman, 5 feet 4 inches height, sunken eyes, open nostrils, wide mouth, missing front teeth, curved legs & walking leaning to the left, the latter escaped with a "nabot", a chain & thumb-grips. Those who recognize them, are requested to stop & transfer them to the nearest dungeons & with the greatest possible safety, & to give notice to Sieur Dorlic at Maribaroux."

Boukman #7 : December 19, 1780 "Bouqueman" is a 55 year old Congo :

"Au Fort-Dauphin, est entré à la Geole (...) le 5, Louis, Congo, étampé sur le sein droit IVCHEREAU, âgé de 30 ans, se disant appartenir à l'Habitation de M. de Juchereau, au Trou ; Bouqueman, même nation, âgé de 55 ans, étampé sur le sein droit FLEURY, se disant appartenir à M. de Fleury, à Jacquesy." (33)Translation :

"At Fort-Dauphin, entered the jail (...) on the 5th, Louis, Congo, stamped on the right breast IVCHEREAU, aged 30, claiming to belong to Mr. Juchereau's Estate at Trou ; Bouqueman, same nation [meaning Congo], 55 years old, stamped on the right breast FLEURY, claiming to belong to Mr. Fleury at Jacquesy [North-East] "

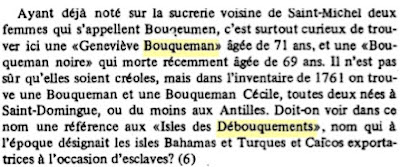

Boukman #8, 9 : in 1783, two other White women named "Bouqueman" and "Bouquemen" are found on the inventory of La Sucrerie Baudin of Quartier Morin (Norh) :

"Ayant déjà noté sur la sucrerie voisine de Saint-Michel deux femmes qui s'appellent Bouquemen, c'est surtout curieux de trouver ici une "Geneviève Bouqueman" âgée de 71 ans, et une "Bouqueman noire" qui morte récemment âgée de 69 ans. Il n'est pas sûr qu'elles soient créoles, mais dans l'inventaire de 1761 on trouve une Bouqueman et une Bouqueman Cécile, toutes deux nées à Saint-Domingue, ou du moins aux Antilles. Doit-on voir dans ce nom une référence aux "Isles des Débouquements", nom qui à l'époque désignait les isles Bahamas et Turques et Caïcos exportatrices à l'occasion d'esclaves?" (34)Translation :

"Having already noted on the nearby Saint-Michel sugar plantation two women called Bouquemen is especially curious to find here a "Genviève Bouqueman", 71 years old, and a "Bouqueman noire" who recently died at the age of 69. It isn't sure whether they were Creoles, but in the 1761 inventory, we've found a Bouqueman and Bouqueman Cécile, both born in Saint Domingue, at least in the West Indies. Should we see in this name a reference to the "Isles of Débouquements", a name which at that time meant the Bahamas islands and Turks & Caicos, at the time slave exporters?

Boukman #10, 11 : On August 30, 1812, in New York, Marie Bouquement, the mother of Adèle Bouquement who remained in Saint Domingue, was buried in "Catholic ground" :

"Marie Bouquement died the last week in August, 1812. She was buried on August 30th of that year in the "Catholic ground," the new cemetery at Prince and Mulberry Streets where the Cathedral of St. Patrick was being built." (35)

Marie Bouquement was born in 1757 in the colony of Saint Domingue ; more specifically in Saint Marc, in the Artibonite region. Like her mother Zénobie Julien, she was a Creole. Her grandmother Tonette, was born in "Africa". So, no islamic link can be established with her Bouquement surname, which was also written Boucman. (36) Moreover Marie Bouquement was the aunt of Pierre Toussaint, beatified asVenerable by Pope John Paul II on December 17, 1996.

(Venerable Pierre Toussaint)

Source : Bishop Norbert Dorsey, CP. Pierre Toussaint of New York : Slave and Freedman. New York, 2014.

Freed on January 20, 1796, Marie Bouquement landed in New York in 1797 at the age of 40. (37) She accompanied members of the Bérard family of whom she was captive (slave) a year earlier. The young captive (slave) Pierre Toussaint, son of her little sister Ursule Julien Toussaint, was among the travellers. Marie Bouquement learned how to read from the Bérards, and not due to any sort of islamic influence. Such was the case for her mother Zénobie, her sister Ursule and her nephew Pierre Toussaint.

These letters refute the lie that the Saint Domingue settlers punished the captives (slaves) who knew how to read. Lie on which is based the revisionist thesis of a literate Boukman Dutty, and that of a false affiliation of writing in the colonies to islam. After all, Pierre Toussaint, a devoted catholic who became prosperous, financially contributed to the construction of New York's Old St. Patrick Cathedral. Deeds of this type would render him worthy of being beatified. Worth noting that Pierre Toussaint's genealogical data differs from what most historians advocate.**

(Letter from Zénobie Julien to her grandson Pierre Toussaint)

Source : Pierre Toussaint Papers, NY Public Library. in : Jean Fouchard. Les marrons du syllabaire. (2ème édition) Port-au-Prince, 1988. planche 8.

(Letter from Pierre Toussaint to William Schuyler)

Source : Pierre Toussaint Papers, NY Public Library. in : Jean Fouchard. Les marrons du syllabaire. (2ème édition) Port-au-Prince, 1988. planche 7. These letters refute the lie that the Saint Domingue settlers punished the captives (slaves) who knew how to read. Lie on which is based the revisionist thesis of a literate Boukman Dutty, and that of a false affiliation of writing in the colonies to islam. After all, Pierre Toussaint, a devoted catholic who became prosperous, financially contributed to the construction of New York's Old St. Patrick Cathedral. Deeds of this type would render him worthy of being beatified. Worth noting that Pierre Toussaint's genealogical data differs from what most historians advocate.**

Boukman #12 : in 1816,*** "Bouqueman" is King Henry's Lieutenant at Ennery (Center) :

"Lieutenant du Roi à Ennery.

M. de Bouqueman, capitaine, C...

M. Toussaint Guillaume, sous-lieut, adjudant d'armes.

(...)

Ordre Royal et Militaire de Saint HENRY, créé le 20 Avril 1811.

Promotion du 28 Octobre 1815, an douze.

Messieurs,

(...)

de Jean Cochet.

d'Étienne Gilot.

de Bouqueman.

de Julien Gillot.

de Lubin."

Translation :M. de Bouqueman, capitaine, C...

M. Toussaint Guillaume, sous-lieut, adjudant d'armes.

(...)

Ordre Royal et Militaire de Saint HENRY, créé le 20 Avril 1811.

Promotion du 28 Octobre 1815, an douze.

Messieurs,

(...)

de Jean Cochet.

d'Étienne Gilot.

de Bouqueman.

de Julien Gillot.

de Lubin."

M. de Bouqueman, captain, C...

M. Toussaint Guillaume, 2nd-lieut, adjutant of arms.

(...)

Royal and Military Order of Saint HENRY, created April 20, 1811.

Promotion of October 28, 1815, year twelve.

Messieurs,

(...)

de Jean Cochet.

d'Étienne Gilot.

de Bouqueman.

de Julien Gillot.

de Lubin." (38)

As we have seen, there were people of all races and colors, of both sexes, of all ages, and of various ethnicities called Boukman in the colony of Saint Domingue. For Boukman was a common name no different than Jean-Jacques or Joseph, etc. No element of this name had a link to either the English language or the island of Jamaica. In an up-coming article, we will lay down the origin of the Boukman surname, how it entered the French language, then assigned to the captives (slaves).

The Dutty surname is viewed, particularly in English-speaking caribbean countries, as a proof that Boukman originated from Jamaica. Thus, reinforcing the islamic falsehood. Like many, I long viewed a Jamaican affiliation to Haitian hero Boukman as a bridge to help fill the cultural and historical gap between Haiti and the caribbean world. But such gap cannot be filled by fabrications that, sooner or later, will shatter,**** but only by historical truth such as the caribbean origin of Haiti's King Henry (Christophe) who "came from the island of Grenada", (39) according to his own secretary, the Baron Pompée-Valentin de Vastey ; or by the use of factual resistance by caribbean captives, which the Saint Domingue archives have plenty of, like this Jamaican, in 1780, that went marooned from his plantation in Morne-Rouge, place of the gathering that sparked the Haitian revolution :

4- "Dutty" in "Boukman Dutty" or "Dutty Boukman" is unfounded

The Dutty surname is viewed, particularly in English-speaking caribbean countries, as a proof that Boukman originated from Jamaica. Thus, reinforcing the islamic falsehood. Like many, I long viewed a Jamaican affiliation to Haitian hero Boukman as a bridge to help fill the cultural and historical gap between Haiti and the caribbean world. But such gap cannot be filled by fabrications that, sooner or later, will shatter,**** but only by historical truth such as the caribbean origin of Haiti's King Henry (Christophe) who "came from the island of Grenada", (39) according to his own secretary, the Baron Pompée-Valentin de Vastey ; or by the use of factual resistance by caribbean captives, which the Saint Domingue archives have plenty of, like this Jamaican, in 1780, that went marooned from his plantation in Morne-Rouge, place of the gathering that sparked the Haitian revolution :

"Un Nègre nommé Lubin, créole de la Jamaïque, âgé d'environ 24 ans, taille de 5 pieds 4 pouces, étampé sur le sein droit GUILLAUME COSQUIER, est parti maron depuis environ trois semaines avec un canot de 17 pieds de long. Ceux qui le reconnoîtront, sont priés de le faire arrêter & d'en donner avis à M. Guillaume Cosquier, Habitant au Morne-Rouge." (40)Translation :

"A Negro called Lubin, creole from Jamaica, aged roughly 24, 5 feet 4 inches high, stamped on the right chest GUILLAUME COSQUIER, went marooned around three weeks ago on a 17-foot canoe. Those who recognize him, please have him arrested & send for M. Guillaume Cosquier, residing at Morne Rouge."

So how did the Dutty surname enter the picture, one might ask? Well, in 1853, Dutty was attached to Boukman as a surname by Haitian author Céligny Ardouin who provided no reference :

* According to the academic French dictionary Dictionnaire Littré de la langue française, Bouc's origin can be traced back to Wallon, a Belgian language. (Littré, 1976 : 379).

** Pierre Toussaint's blind dedication to this Bérard family who put him and his family in captivity (slavery) is despicable. His acceptance of white domination and his rejection of black emancipation is reprehensible. However, his involvement in pioneered charities such as schooling and orphanage for New York's Black children makes him esteemed. That's why we give him attention in this study.

2) Pierre Toussaint's original owner was Jean-François Bérard du Pithon. From 1781 to 1788, Jean-François Bérard du Pithon was "infantry captain and commander of the La Petite-Rivière de l'Artibonite parish", where he lived for 44 years. Due to health issues, he took leave on May 14, 1785 for treatment in Bordeaux, France. He received successive leave extensions from the army, until his retirement in 1788, (48) that is 3 years before the eruption of the Haitian Revolution in 1791.

3) In 1793-1794, Civil Commissioner Sonthonax freed the Saint Domingue captives (slaves). However, the newly freed were required to remain on their respective plantations as employees. Pierre Toussaint and his family remained faithful to the Bérard estate, although many other former captives (slaves) left the place.

On July 5, 1795, the patriarch Jean-François Bérard du Pithon died in France. (49) All of his children were then settled in Paris, except his eldest son, Jean-Jacques Bérard du Pithon who was the last heir still on the estate. He would gain his father's former captives (slaves) who have become his servants and employees.

On April 11, 1796, Jean-Jacques Bérard married his second wife Adélaïde Marie Elisabeth Bossard, a native of Dondon (Saint Domingue), also on her second marriage. A year later, August 21, 1797, fleeing Saint Domingue's revolutionary unrest, the couple exiled in New York. (50) Did accompany him, among others, 5 servants including Pierre Toussaint, his little sister Rosalie Toussaint, and their Aunt Marie Bouquement. Although freed under Saint Domingue law, these servants have nevertheless chosen to follow their former masters abroad where they would once more become captives (slaves), because they do not possess, with the exception of Marie Bouquement, individual freedom papers. They wrongly qualify as Haitians, Pierre Toussaint and those Black Dominguois who lack the nobility of a desalinian nationality.

Having returned to Saint Domingue to take care of his business, Jean-Jacques Bérard died of illness on September 12, 1799. (51) His widow Élisabeth Bossard Bérard then remarried on August 11, 1802 with Jean-Baptiste Gabriel Nicolas, an expatriate from Aquin, Saint Domingue. This particular union got formalized on January 15, 1803. (52) And thanks to his job as a high society hairdresser, Pierre Toussaint then financially supported this couple in need. Élisabeth Bossard, known as Madame Bérard Nicolas, emancipated Pierre Toussaint on July 2, 1807, at the French Consulate in New York (53) ; and not on her deathbed as everyone claim. (54) This freedom will be validated by the consular authorities on July 14th of that year.

4) Hannah Farnham Sawyer Lee, the first to write about Pierre Toussaint, said that the latter, whom she knew, was born in 1766. (55) Since then, this date has been retained by historians. The 1766 hypothesis means that Pierre Toussaint was supposedly 9 years younger than his maternal aunt Marie Bouquement. Because the latter, 40 years old when she arrived in New York in 1797, was born in 1757, as we pointed out. But this 9 year gap is not conceivable, since Marie Bouquement was the first born of Zénobie Julien, and the big sister of Ursule Toussaint, the mother of Pierre. Moreover, Pierre Toussaint was not even the first child of his mother Ursule. He was the third, following his elder sister Marie-Louise Pacaud and their elder brother Antoine aka Toussaint. (56)

We will even say that it is impossible that Pierre Toussaint was born in 1766, since his godmother was born 10 years after the proposed date. That godmother whom Pierre Toussaint simply called Mademoiselle De Pointe and the Parisians knew as Aurore Bérard, (57) she was in fact Marie Elizabeth Etiennette Bérard, the last daughter of Jean-François Bérard and his wife Marguerite Victoire Magnan. Her baptismal certificate testifies that she was born on December 8, 1776 in La Petite-Rivière de l'Artibonite.

Marie Elizabeth Etiennette Bérard, known as Aurore, was a minor when she became godmother to Pierre Toussaint. She herself had a minor godmother (aged 15), her first cousin Marie-Louise Elizabeth François Audigé, also born on December 8, but in 1761. (58) Aurore's godmother and maternal cousin is the daughter of Marie Louise Gabrielle Magnan, whom 3 days after giving birth to her, died of complications on December 11, 1761. (59)

5) Pierre Toussaint's exact year of birth is much more difficult to determine. The author Arthur Jones (60) relies on the fact that Pierre Toussaint, the hairdresser, entrusted to Madame Brochet, a Parisian client in transit in New York, that he was a playmate of his godmother Mademoiselle De Pointe aka Aurore Bérard. (61) According to Arthur Jones, 5 years would be the maximum age difference for a play relationship between 2 children. So, his godmother Aurore Bérard being born in 1776, Pierre Toussaint was then born at the most, 5 years later, in 1781.

Arthur Jones also analyzed the freedom that Pierre Toussaint provided to his little sister Rosalie, so that she would be a free person at her wedding, a week later, with Jean Noël. Rosalie Toussaint's May 21, 1811 emancipation paper reveals that she was 25 years old that year. This means that she was born in 1786. Arthur Jones later deduced that Pierre Toussaint was his sister Rosalie's playmate. (62) Indeed, in their youth in Saint Domingue, the 2 followed Pierre's young godmother around, and often danced for her amusement. (63) Therefore, according to Jones, Pierre Toussaint would be at most 5 years older than his sister Rosalie born in 1786. Thus, Pierre Toussaint was born at the latest in 1781.

We believe that Pierre Toussaint's date of birth is actually between 1781 and 1785. The year of 1781, until proven otherwise, remains the most plausible median date. But we can not say as much for 1766 who would give Pierre Toussaint 20 years more than his sister Rosalie.

6) If the year of birth of Pierre Toussaint, according to our analysis, is between 1781 and 1785, his birthday offers more certainty. Historians have retained June 27. However, author Bishop Norbert Dorsey raises doubts. (64) He argues that the June 27th determination comes from a happy birthday wish that Euphemia, Pierre Toussaint's niece and adoptive daughter addressed her uncle in a letter dated June 27, 1825. But, continued the author , Euphemia Toussaint used to write to her uncle on Fridays, and that Pierre Toussaint read those letters on Saturdays. Therefore it exists an uncertainty between the day that letter was written (Friday) and the day it was read Saturday). Which one was the said birthday?

After having taken a look at this, we say June 27th is the right day, since Euphemia's letter was written on a Monday. Contrary to Bishop Norbert Dorsey's argument, June 27, 1825 was a Monday, not a Friday. Thus, Euphemia's letter was written and read the same day, June 27, birthday of her uncle Pierre Toussaint.

*** 1816 was clearly 12 years into the free state of Hayti. But Lieutenant de Bouqueman was born and named in the Saint Domingue colony.

"Toussaint fit choix de ses plus intimes amis+, Jean-François Papillon, Georges Biassou, Boukman Dutty et Jeannot Billet. Les conjurés se réunirent ct se distribuèrent les rôles. Plus rusé que les autres, Jean-François obtint le premier rang++, Biassou le second; et Boukman et Jeannot, plus audacieux, se chargèrent de diriger les premiers mouvements." (41)Translation :

"Toussaint chose some of his closest friends+, Jean-François Papillon, Georges Biassou, Boukman Dutty and Jeannot Billet. They gathered and distributed the roles. Jean-François, the sneakiest, obtained the highest rank++. Biassou, was second in command ; while Boukman and Jeannot, the most audacious, were in charge of the first attacks."

It

is unwise to take Ardouin at face value, knowing that he was

writing about events that took place 62 years earlier. To this day, no

archival data supports links Boukman to the name Dutty. As for the claim

that Dutty was the name of a Jamaican planter, it is unproven as well.

Due

to the English nature of the name Dutty found in French speaking Saint

Domingue (Haiti), one is tempted to attribute an external English origin to

that name. But, even if Boukman was also named Dutty, that wouldn't

automatically mean that he came from an English speaking colony.

Because, historical data shows that name in the colony with no connection to

an English source. For example, in 1766 (25 years before Bwa Kayiman) we

had this runaway ad in Fort Dauphin (Fort Liberté, Northeastern Saint Domingue) for

a Mulatto from the French colony of Martinique named Jean Dutie:

"Un Mulâtre, se disant libre, de la Martinique, & se nommer Jean Dutie, étampé sur le sein droit RIMEAV, & sur le gauche illisiblement." (42)Translation :

"A Mulatto, claims to be free, from Martinique, and says to be named Jean Dutie, stamped on the right chest RIMEAV, and on the left illegibly."

This is the full runaway ad. The Jean Dutie reference is on the bottom :

Aside

from Jean Dutie, there were several runaway ads for captives stamped DUTY. And

never, in these case, have we found a reference to an English filiation

to those captives, nor to their owners. For example, the following 1767 runaway ad (24 years before Bwa Kayiman)

is about Pallanqué, a captive identified as Portuguese, that was

stamped DUTY and whose owner was Sr. Duty from Port-de-Paix (North-Western

Saint Domingue) :

"Un Negre Portugais, nommé Pallanqué, étampé sur les deux seins DUTY & au dessous PP, âgé d'environ 40 ans, taille de 5 pieds 5 pouces, rouge de peau, est maron depuis le 28 avril. Ceux qui le reconnoîtront sont priés de le faire arrêter & d'en donner avis au Sr. Duty, Passager du Port-de-Paix, demeurant audit lieu; il y aura une quadruple de récompense." (43)Translation :

"A Portuguese Negro, named Pallanqué, stamped on both chest DUTY & on the bottom PP, aged roughly 40, hight 5 feet 5 inches, light skinned, went marooned on April 28th. Those who recognize him are asked to have him arrested & send a note to Sr. Duty, visiting from Port-de-Paix, residing at the said place ; there will be four times the reward."

In

this case, Pallanqué, the captive, can be given his owner's surname and be called

Pallanqué Duty, as was the norm in the colony. Just like Boukman, most modern people would easily believe, due to the

English-sounding Duty surname, that he hailed from an English colony.

But this runaway ad, in showing that Pallanqué Duty, actually came

from a Portuguese-speaking territory, also proves that the name Dutty, arbitrarily assigned to Boukman by Céligny Ardouin, isn't proof of an English origin. As for the owner, Sr. Duty,

nothing in his 1767 runaway ad suggests that he was English, or even foreign to the colony.

Here is another ad referring to the same Sr. Duty. Payed for the Port-de-Paix prison, this ad is dated August 1781, that is 10 years prior to Bois Caïman :

Here is another ad referring to the same Sr. Duty. Payed for the Port-de-Paix prison, this ad is dated August 1781, that is 10 years prior to Bois Caïman :

"'Le 11, Jean-Baptiste, Congo, étampé sur le sein droit I DVTY et au-dessous PP, âgé d'environ 25 ans, taille de 4 pieds 9 pouces, se disant avoir appartenu au Sr Duty et actuellement au Sieur Dupon, Habitant au Borgne." (44)Translation :

"On the 11th, Jean-Baptiste, Congo, stamped on the right breast I DVTY and below PP, about 25 years old, 4 feet 9 inches tall, claiming to have belonged to Sr Duty and now to Sieur Dupon , Living in Borgne."

Moreover,

we've found various other cases of captives stamped DUTY, and, again, with no

English linkage, proving that the name Duty enter French genealogy long

before the establishment of the Transatlantic slavery and the colony of

Saint Domingue :

a) Stamped JOYNEAU & DUTY :

"Un Nègre appellé Bouis Chouchou, appartenant aux mineurs Joyneau, étampé JOYNEAU & DUTTY, affermé au Sieur Videlet, habitant au quartier de Saint-Louis. Ceux qui le reconnaîtront, sont priés de le faire arrêter. Il y aura récompense." (45)Translation :

"A Negro called Bouis Chouchou, belonging to the Joyneau miners, stamped JOYNEAU & DUTTY, leased to Sieur Videlet, living in the Saint-Louis neighborhood. Those who recognize him, are asked to have him arrested. There will be reward."b) 2 captives stamped DUTY :

"Toussaint Dupon âgé de 28 ans : Toussaint Casalis âgé de 24 ans : César âgé de 26 ans ; ces six derniers sont de nation Congo, & sont étampés E DUPON : Laurent de nation Congo, âgé de 40 ans, étampé A CRUCHET, Léon âgé de 18 ans : Monplaisir âgé de 23 ans : Marsias & Darius, âgé de 20 ans ; ces quatre derniers sont de nation Congo, & sont étampés E. DUPON : Augustin âgé de 22 ans, étampé DUTY : Augustin de nation Mayombé, âgé de 22 ans, étampé E DUPON. (...) Joseph âgé de 26 ans, étampé DUTY : tous les Nègres ci-dessus sont partis marrons de l'habitation de madame veuve Dupont, dans les hauteurs du Bas de Saint-Anne : en donner des nouvelles à ladite Dame, ou à M. Louis Foucher au Cap-Français." (46)Translation :

"Toussaint Dupon aged 28: Toussaint Casalis aged 24 : Caesar aged 26 ; The last six are of the Congo nation, and are stamped DUPON: Laurent of Congo nation, aged 40, stamped A CRUCHET, Léon aged 18 : Monplaisir aged 23 : Marsias & Darius, aged 20; These last four are of the Congo nation, and are stamped E. DUPON : Augustin aged 22, stamped DUTY : Augustin of Mayombé nation, 22 years old, stamped E DUPON (...) Joseph aged 26, stamped DUTY : All the negroes above went maroon from the habitation of Madame Dupont, in the heights of Lower Saint-Anne, give news to the said Lady, or to M. Louis Foucher at Cap-Francais."

c) Stamped DOUTTÉ & S. LAPALIERE :

"François de nation Congo, âgé d'environ 40 ans, de la taille de 5 pieds 4 pouces, étampé DOUTTÉ & S. LAPALIERE, la dernière étampe ayant la forme d'un croissant, est parti marron depuis un an..." (47)Translation :

"Francois of Congo nation, about 40 years old, sized 5 feet 4 inches, stamped DOUTTÉ & S. LAPALIERE, the last stamp having the shape of a crescent, went maroon since last year..."

* According to the academic French dictionary Dictionnaire Littré de la langue française, Bouc's origin can be traced back to Wallon, a Belgian language. (Littré, 1976 : 379).

** Pierre Toussaint's blind dedication to this Bérard family who put him and his family in captivity (slavery) is despicable. His acceptance of white domination and his rejection of black emancipation is reprehensible. However, his involvement in pioneered charities such as schooling and orphanage for New York's Black children makes him esteemed. That's why we give him attention in this study.

False information persists, particularly as to the date and place of birth of Pierre Toussaint and the name of his original owner. Let's dispel them briefly.

1) Everyone agrees that Pierre Toussaint was born in captivity (slavery) in Saint Domingue's Artibonite region. However, it is false to say that he is a native of Saint Mark. For Pierre Toussaint was instead born in the La Petite-Rivière de l'Artibonite locality, which is not a satellite of Saint Marc, the big city. As these 2 maps illustrate, La Petite-Rivière de l'Artibonite and Saint Marc are 2 distinct places :

1) Everyone agrees that Pierre Toussaint was born in captivity (slavery) in Saint Domingue's Artibonite region. However, it is false to say that he is a native of Saint Mark. For Pierre Toussaint was instead born in the La Petite-Rivière de l'Artibonite locality, which is not a satellite of Saint Marc, the big city. As these 2 maps illustrate, La Petite-Rivière de l'Artibonite and Saint Marc are 2 distinct places :

(Location of La Petite-Rivière de l'Artibonite, Haiti)

Source : https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Petite-Rivi%C3%A8re-de-l%27Artibonite

(Location of the city of Saint Marc, Haiti)

Source : https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saint-Marc_(Ha%C3%AFti)2) Pierre Toussaint's original owner was Jean-François Bérard du Pithon. From 1781 to 1788, Jean-François Bérard du Pithon was "infantry captain and commander of the La Petite-Rivière de l'Artibonite parish", where he lived for 44 years. Due to health issues, he took leave on May 14, 1785 for treatment in Bordeaux, France. He received successive leave extensions from the army, until his retirement in 1788, (48) that is 3 years before the eruption of the Haitian Revolution in 1791.

3) In 1793-1794, Civil Commissioner Sonthonax freed the Saint Domingue captives (slaves). However, the newly freed were required to remain on their respective plantations as employees. Pierre Toussaint and his family remained faithful to the Bérard estate, although many other former captives (slaves) left the place.

On July 5, 1795, the patriarch Jean-François Bérard du Pithon died in France. (49) All of his children were then settled in Paris, except his eldest son, Jean-Jacques Bérard du Pithon who was the last heir still on the estate. He would gain his father's former captives (slaves) who have become his servants and employees.

On April 11, 1796, Jean-Jacques Bérard married his second wife Adélaïde Marie Elisabeth Bossard, a native of Dondon (Saint Domingue), also on her second marriage. A year later, August 21, 1797, fleeing Saint Domingue's revolutionary unrest, the couple exiled in New York. (50) Did accompany him, among others, 5 servants including Pierre Toussaint, his little sister Rosalie Toussaint, and their Aunt Marie Bouquement. Although freed under Saint Domingue law, these servants have nevertheless chosen to follow their former masters abroad where they would once more become captives (slaves), because they do not possess, with the exception of Marie Bouquement, individual freedom papers. They wrongly qualify as Haitians, Pierre Toussaint and those Black Dominguois who lack the nobility of a desalinian nationality.

Having returned to Saint Domingue to take care of his business, Jean-Jacques Bérard died of illness on September 12, 1799. (51) His widow Élisabeth Bossard Bérard then remarried on August 11, 1802 with Jean-Baptiste Gabriel Nicolas, an expatriate from Aquin, Saint Domingue. This particular union got formalized on January 15, 1803. (52) And thanks to his job as a high society hairdresser, Pierre Toussaint then financially supported this couple in need. Élisabeth Bossard, known as Madame Bérard Nicolas, emancipated Pierre Toussaint on July 2, 1807, at the French Consulate in New York (53) ; and not on her deathbed as everyone claim. (54) This freedom will be validated by the consular authorities on July 14th of that year.

4) Hannah Farnham Sawyer Lee, the first to write about Pierre Toussaint, said that the latter, whom she knew, was born in 1766. (55) Since then, this date has been retained by historians. The 1766 hypothesis means that Pierre Toussaint was supposedly 9 years younger than his maternal aunt Marie Bouquement. Because the latter, 40 years old when she arrived in New York in 1797, was born in 1757, as we pointed out. But this 9 year gap is not conceivable, since Marie Bouquement was the first born of Zénobie Julien, and the big sister of Ursule Toussaint, the mother of Pierre. Moreover, Pierre Toussaint was not even the first child of his mother Ursule. He was the third, following his elder sister Marie-Louise Pacaud and their elder brother Antoine aka Toussaint. (56)

We will even say that it is impossible that Pierre Toussaint was born in 1766, since his godmother was born 10 years after the proposed date. That godmother whom Pierre Toussaint simply called Mademoiselle De Pointe and the Parisians knew as Aurore Bérard, (57) she was in fact Marie Elizabeth Etiennette Bérard, the last daughter of Jean-François Bérard and his wife Marguerite Victoire Magnan. Her baptismal certificate testifies that she was born on December 8, 1776 in La Petite-Rivière de l'Artibonite.

(Baptismal extract of Marie Elizabeth Etiennette Bérard aka Aurore Bérard)

Source

: ANOM, État civil. Saint-Domingue, Petite Rivière de l'Artibonite,

1776 ; URL :

http://anom.archivesnationales.culture.gouv.fr/caomec2/osd.php?territoire=SAINT-DOMINGUE&commune=PETITE-RIVIERE-DE-L%27ARTIBONITE&annee=1776Marie Elizabeth Etiennette Bérard, known as Aurore, was a minor when she became godmother to Pierre Toussaint. She herself had a minor godmother (aged 15), her first cousin Marie-Louise Elizabeth François Audigé, also born on December 8, but in 1761. (58) Aurore's godmother and maternal cousin is the daughter of Marie Louise Gabrielle Magnan, whom 3 days after giving birth to her, died of complications on December 11, 1761. (59)

5) Pierre Toussaint's exact year of birth is much more difficult to determine. The author Arthur Jones (60) relies on the fact that Pierre Toussaint, the hairdresser, entrusted to Madame Brochet, a Parisian client in transit in New York, that he was a playmate of his godmother Mademoiselle De Pointe aka Aurore Bérard. (61) According to Arthur Jones, 5 years would be the maximum age difference for a play relationship between 2 children. So, his godmother Aurore Bérard being born in 1776, Pierre Toussaint was then born at the most, 5 years later, in 1781.

Arthur Jones also analyzed the freedom that Pierre Toussaint provided to his little sister Rosalie, so that she would be a free person at her wedding, a week later, with Jean Noël. Rosalie Toussaint's May 21, 1811 emancipation paper reveals that she was 25 years old that year. This means that she was born in 1786. Arthur Jones later deduced that Pierre Toussaint was his sister Rosalie's playmate. (62) Indeed, in their youth in Saint Domingue, the 2 followed Pierre's young godmother around, and often danced for her amusement. (63) Therefore, according to Jones, Pierre Toussaint would be at most 5 years older than his sister Rosalie born in 1786. Thus, Pierre Toussaint was born at the latest in 1781.

We believe that Pierre Toussaint's date of birth is actually between 1781 and 1785. The year of 1781, until proven otherwise, remains the most plausible median date. But we can not say as much for 1766 who would give Pierre Toussaint 20 years more than his sister Rosalie.

6) If the year of birth of Pierre Toussaint, according to our analysis, is between 1781 and 1785, his birthday offers more certainty. Historians have retained June 27. However, author Bishop Norbert Dorsey raises doubts. (64) He argues that the June 27th determination comes from a happy birthday wish that Euphemia, Pierre Toussaint's niece and adoptive daughter addressed her uncle in a letter dated June 27, 1825. But, continued the author , Euphemia Toussaint used to write to her uncle on Fridays, and that Pierre Toussaint read those letters on Saturdays. Therefore it exists an uncertainty between the day that letter was written (Friday) and the day it was read Saturday). Which one was the said birthday?

After having taken a look at this, we say June 27th is the right day, since Euphemia's letter was written on a Monday. Contrary to Bishop Norbert Dorsey's argument, June 27, 1825 was a Monday, not a Friday. Thus, Euphemia's letter was written and read the same day, June 27, birthday of her uncle Pierre Toussaint.

*** 1816 was clearly 12 years into the free state of Hayti. But Lieutenant de Bouqueman was born and named in the Saint Domingue colony.

**** Here is a perfect example of the dishonest fabrications that circulate about Boukman's so-called Jamaican origin. This falsified story came from the CARICOM Reparations Commission, a branch of CARICOM (The Caribbean Community), an international institution made up of 15 member states, and many other partners and observers. The CARICOM Reparations Commission, proposed in a revisionist tweet, a photo of Boukman, the fabricated Jamaican literate :

However, photography was not even invented in 1791, date of the death of Boukman Dutty. Moreover, the proposed picture that bears the stamp of the CARICOM Reparations Commission, is in fact that of Ño Remigio Herrera "Adechina", a legendary Afro-Cuban Babalawo :

This picture was taken in Havana (Cuba) in 1891, exactly 100 years after Boukman's death. For Ño Remigio Herrera, known as "Adechina" was born in Nigeria around 1811. He was transported as a captive (slave) to La Regla, Cuba in 1830 where he introduced the ancient cult of Ifa. And thanks to his talents as Babalawo (great leader of the traditional Yoruba religion), he won his freedom and became a successful businessman. He died of old age on January 27, 1905. (65)

Here are more photos of Ño Remigio Herrera "Adechina", and that of his daughter Josefa "Pepa" Herrera, also great traditionalist official :

Source : https://face2faceafrica.com/article/remigio-herrera-the-nigerian-slave-who-heavily-influenced-cuba-as-a-mystic-in-the-1800s

Source : https://myspace.com/spectralphil/mixes/classic-awos-ni-orunmila-iyalochas-y-babalochas-famosos-454596

Here is another falsification example. Despite the evidence that photography was not invented during the lifetime of Boukman, who died in November 1791, this fake photo linked to the name Boukman circulates online :

The falsifiers always make sure they trim the original photo, in order to hide the inscriptions showing that it is not Boukman :

But the handwritten line "Fort de France (Martinique)" does not match the printed description of a "Haitian sorcerer". This second photo specifies the model's identity. He is Papa Pierre, a Papa Lwa, a Houngan or great Haitian traditionalist official :

This second photo of Papa Pierre, taken in 1905 or 1908, according to different sources. It even served as a postcard :

The initials F. D. suggest that this postcard (not the photo) originates from the "indigenist" era of François Duvalier (1957-1971). In short, we are not at the end of our troubles. For the dishonest and the lazy, in search of notoriety or legitimacy, will not stop falsifying historical documents, in the most flagrant manner.

+ Ardouin's statement is untrue, because Toussaint, a former slave turned slaveowner, wasn't the mastermind of the revolution as many like to think. It was Jean-Jacques, commander of the des Manquets (Noé) plantation in L'Acul (North) that engineered the whole thing over close to a decade. (To be developped later)]

(Tweet and inaccurate picture proposed by CARICOM Reparations)

Source : https://twitter.com/CariReparations/status/782675957828071424/photo/1However, photography was not even invented in 1791, date of the death of Boukman Dutty. Moreover, the proposed picture that bears the stamp of the CARICOM Reparations Commission, is in fact that of Ño Remigio Herrera "Adechina", a legendary Afro-Cuban Babalawo :

(Picture of Ño Remigio Herrera taken in 1891)

Sources : Museum of La Regla. In : David H. Brown. Santeria Enthroned: Art, Ritual, and Innovation in an Afro-Cuban Religion. Chicago, 2003. p. 64. (fig. 2.1) ; http://theasefountain.tumblr.com/post/5222527904/diasporic-heroes-4-adechina-remigio-herrera This picture was taken in Havana (Cuba) in 1891, exactly 100 years after Boukman's death. For Ño Remigio Herrera, known as "Adechina" was born in Nigeria around 1811. He was transported as a captive (slave) to La Regla, Cuba in 1830 where he introduced the ancient cult of Ifa. And thanks to his talents as Babalawo (great leader of the traditional Yoruba religion), he won his freedom and became a successful businessman. He died of old age on January 27, 1905. (65)

Here are more photos of Ño Remigio Herrera "Adechina", and that of his daughter Josefa "Pepa" Herrera, also great traditionalist official :

Source : https://face2faceafrica.com/article/remigio-herrera-the-nigerian-slave-who-heavily-influenced-cuba-as-a-mystic-in-the-1800s

Source : https://myspace.com/spectralphil/mixes/classic-awos-ni-orunmila-iyalochas-y-babalochas-famosos-454596

(Jofefa "Pepa" Herrera, daughter of Ño Remigio Herrera "Adechina")

Source : Museum of La Regla. In : David H. Brown. Santeria Enthroned: Art, Ritual, and Innovation in an Afro-Cuban Religion. Chicago, 2003. p. 66. (fig.2.2) ; https://myspace.com/spectralphil/mixes/classic-awos-ni-orunmila-iyalochas-y-babalochas-famosos-454596/photo/182468643Here is another falsification example. Despite the evidence that photography was not invented during the lifetime of Boukman, who died in November 1791, this fake photo linked to the name Boukman circulates online :

(Falsified photo claimed to represent Boukman Dutty, in 2017)

Source

:

https://agoraafricaine.info/2017/12/13/en-1791-le-pretre-haitien-dutty-bookman-se-servit-du-vaudou-pour-vaincre-les-armees-de-louis-14/The falsifiers always make sure they trim the original photo, in order to hide the inscriptions showing that it is not Boukman :

"Papa Loi (Haitian sorcerer) priest of Vodou Religion." (Transl.)Source : https://universalayititoma.tumblr.com/page/7

But the handwritten line "Fort de France (Martinique)" does not match the printed description of a "Haitian sorcerer". This second photo specifies the model's identity. He is Papa Pierre, a Papa Lwa, a Houngan or great Haitian traditionalist official :

"A Papa-Loi (Sorcerer) - Papa Pierre" (Transl.)Sources : Kiran Jayaram. "Digging the Roots, Or, Resistance and Identity Politics of the Mouvman Rasin in Haiti", thesis, 2003, Appendix A. ; https://universalayititoma.tumblr.com/page/32

This second photo of Papa Pierre, taken in 1905 or 1908, according to different sources. It even served as a postcard :

(Haitian Postcard of Houngan Papa Pierre)

Source : https://cartespostales.eu/hati/108658-HAITI_-_Un_Papa-Loi__Sorcier__-_Papa_Pierre_-_Pr_tre_Vaudou_-_tr_s_bon__tat.html

; Lewis Ampidu Clorméus. "HAÏTI (1911-1912) : Contribution à une

historiographie". In : Histoire, monde et culturres religieuses. 2012/4

n° 24. pp. 105-130. (p.112) The initials F. D. suggest that this postcard (not the photo) originates from the "indigenist" era of François Duvalier (1957-1971). In short, we are not at the end of our troubles. For the dishonest and the lazy, in search of notoriety or legitimacy, will not stop falsifying historical documents, in the most flagrant manner.

+ Ardouin's statement is untrue, because Toussaint, a former slave turned slaveowner, wasn't the mastermind of the revolution as many like to think. It was Jean-Jacques, commander of the des Manquets (Noé) plantation in L'Acul (North) that engineered the whole thing over close to a decade. (To be developped later)]

++ Contrary to common belief, Boukman wasn't the leader of the

insurrection ; Jean-François (the King) was. Nor was he the second in command ; Biassou (the Vice-Roi) was. See "Boukman wasn't the revolutionary army's leader" for more.

Notes

Notes

(1) https://dictionnaire.reverso.net/francais-definition/bouc

(2) Pamphile de Lacroix. Memoires pour servir a l'histoire de la revolution de Saint-Domingue. (2e édition) Paris, 1820. p.v.

(3) Prophète Joseph. Dictionnaire Haïtien-Français. Montréal, 2003. p.20.

(4) Comte de Chesnel. Encyclopédie militaire et maritime, Volume 1. Paris, 1864. p.57.

(5) Le Dictionnaire Littré de la langue française de 1976, à la page 390.

(6) Moreau de Saint-Méry. Description topographique, physique, civile, politique, Tome 1. Philadelphie, 1796. pp.129-130.

(2) Pamphile de Lacroix. Memoires pour servir a l'histoire de la revolution de Saint-Domingue. (2e édition) Paris, 1820. p.v.

(3) Prophète Joseph. Dictionnaire Haïtien-Français. Montréal, 2003. p.20.

(4) Comte de Chesnel. Encyclopédie militaire et maritime, Volume 1. Paris, 1864. p.57.

(5) Le Dictionnaire Littré de la langue française de 1976, à la page 390.

(6) Moreau de Saint-Méry. Description topographique, physique, civile, politique, Tome 1. Philadelphie, 1796. pp.129-130.

(7) Les affiches américaines of Wednesday July 13, 1768. Issue No.28. p.227.

(8) Jacques Nicolas Bellin. Description des débouquements qui sont au nord de l'isle de Saint Domingue. Paris, 1768. p.2.

(9) Les affiches américaines of Wednesday July 13, 1768. Issue No.28. p.227.

(10) Beaubrun Ardouin. Études sur l'histoire d'Haïti. Volume 1, Paris, 1853. pp.219-220.

(11) Pierre François Page. Traité d'économie politique et de commerce des colonies, Tome 2. Paris, 1801. p.xxxviii

(12) Phillipe Lattre. Campagnes des Français à Saint-Domingue. Paris, 1805. pp.47-48.

(13) « Notes de M. Leclerc, procureur-syndic du Limbé, commissaire du gouvernement près du tribunal criminel du Cap français, sur la brochure de M. Gros », AN, Col. CC9a 5.

(14) Yves Bénot. "The insurgents of 1791, their leaders and the concept of independence". In: David Patrick Geggus, Norman Fiering. The World of the Haitian Revolution. Bloomington, 2009. pp.99-110.

(15) Henri Baptiste Grégoire. De la littérature des Nègres ou recherches de leurs facultés. Paris, 1808. p.107.

(16) Placide Justin, James Barskett (Sir.). Histoire politique et statistique de l'île d'Hayti: Saint-Domingue... Paris, 1826. p.206.

(17) Victor Hugo. Bug-Jargal, Paris 1826. p.43.

(18) Gaspard Théodore Mollien. Histoire ou Saint Domingue. Tome 1. Paris, 1831, réed. 2006. p.72.

(19) Saint-Rémy "Vie de Toussaint-L'Ouverture. Cayes, 1850. p.19.

(11) Pierre François Page. Traité d'économie politique et de commerce des colonies, Tome 2. Paris, 1801. p.xxxviii

(12) Phillipe Lattre. Campagnes des Français à Saint-Domingue. Paris, 1805. pp.47-48.

(13) « Notes de M. Leclerc, procureur-syndic du Limbé, commissaire du gouvernement près du tribunal criminel du Cap français, sur la brochure de M. Gros », AN, Col. CC9a 5.

(14) Yves Bénot. "The insurgents of 1791, their leaders and the concept of independence". In: David Patrick Geggus, Norman Fiering. The World of the Haitian Revolution. Bloomington, 2009. pp.99-110.

(15) Henri Baptiste Grégoire. De la littérature des Nègres ou recherches de leurs facultés. Paris, 1808. p.107.

(16) Placide Justin, James Barskett (Sir.). Histoire politique et statistique de l'île d'Hayti: Saint-Domingue... Paris, 1826. p.206.

(17) Victor Hugo. Bug-Jargal, Paris 1826. p.43.

(18) Gaspard Théodore Mollien. Histoire ou Saint Domingue. Tome 1. Paris, 1831, réed. 2006. p.72.

(19) Saint-Rémy "Vie de Toussaint-L'Ouverture. Cayes, 1850. p.19.

(20) J.-C. Dorsainvil & F.I.C. Manuel d'histoire d'Haiti. Port-au-Prince. 1925. réed.1942. p.64.

(21) "Jean François, Biassou et quelques autres, que leur taille, leur force et d'autres avantages corporels semblaient désigner pour le commandement.” [Translation] : "Jean Francois, Biassou, and some others, whose size, strength, and other bodily advantages seemed to designate to be in command." Beaubrun Ardouin. Études sur l'histoire d'Haïti. Volume 1. Paris, 1853. pp.230-231.

(22) "Ce nègre [Macandal], déjà remarquable par sa taille de titan, sa force herculéenne, l'était encore bien davantage par son origine et son intelligence." [Translation] : "This negro

[Macandal], already remarkable for his size of titan, his Herculean

strength, was still more so by his origin and intelligence." Revue du monde colonial, asiatique et américain: organe politique ..., Volume 12. Paris, 1864. p.448.

(23) "Une négresse de taille gigantesque [Cécile Fatiman] (...) fit son apparition. On eût dit que ses yeux lançaient des étincelles." [Translation] : "A gigantic negress [Cécile Fatiman] (...) made her appearance. One would have said that her eyes threw sparks." Bulletin international des études créoles, Volumes 13-15, AUPELF, 1990 - Creole dialects, French. 24.

(24) "[Henry] Christophe was tall, strong, and handsome, with bright, flashing eyes — "a fine portly looking man," as a British naval officer who visited Haiti in 1818 describes him." Earl Leslie Giggs & Clifford H. Prator (ed). Henry Christophe & Thomas Clarkson: A Correspondance. Berkely & Los Angeles, 1952. pp.38-39.

(25) "Les insurgés du Cul-de-Sac avaient à leur tête un africain, nommé Halaou, d'une taille gigantesque, dune force herculéenne." [Translation] : "The insurgents of Cul-de-Sac had at their head an African, named Halaou, of a gigantic size, of Herculean strength." Thomas Madiou. HIstoire d'Haïti, Tome 1. Port-au-Prince, 1847. p.181.

(26) Mémoire de l'assemblée générale de la partie Française de Saint-Domingue, concernant l'emprunt qu'elle se propose de faire à la Jamaïque. (25 septembre 1791). in : La Gazette de Saint-Domingue. du Mercredi 2 Novembre 1791. Issue No.88. p. 1008.

(27) Garran-Coulon. Rapport sur les troubles de Saint-Domingue, fait au nom de la Commission des colonies, des Comités de salut public, de législation et de marine, réunis. Tome 2. p.246.

(28) Moreau de St Méry. [A.N. COLONIES P.88]" in : Pierre Pluchon. Vaudou, sorciers, empoisonneurs: de Saint-Domingue à Haiti. Paris, 1987. p.185.

(29) (ANOM) Archives Nationale d’Outremer), État civil de St-Domingue, par. 33 (Port-au-Prince/Saint-Domingue), 1757, p./vue 38

(30) David Geggus. “Les esclaves de la plaine du Nord à la veille de la Révolution française, pt 1." in: Revue de la Société haïtienne d'histoire et de géographie, Issues 132-137. Port-au-Prince, 1981. pp. 85-107.

(31) Les Affiches Américaines of February 10, 1776. Issue no. 6, p.69.

(27) Garran-Coulon. Rapport sur les troubles de Saint-Domingue, fait au nom de la Commission des colonies, des Comités de salut public, de législation et de marine, réunis. Tome 2. p.246.

(28) Moreau de St Méry. [A.N. COLONIES P.88]" in : Pierre Pluchon. Vaudou, sorciers, empoisonneurs: de Saint-Domingue à Haiti. Paris, 1987. p.185.

(29) (ANOM) Archives Nationale d’Outremer), État civil de St-Domingue, par. 33 (Port-au-Prince/Saint-Domingue), 1757, p./vue 38

(30) David Geggus. “Les esclaves de la plaine du Nord à la veille de la Révolution française, pt 1." in: Revue de la Société haïtienne d'histoire et de géographie, Issues 132-137. Port-au-Prince, 1981. pp. 85-107.

(31) Les Affiches Américaines of February 10, 1776. Issue no. 6, p.69.

(32) Les Affiches Américaines of October 5, 1779. Issue no. 40, p.0.

(33) Les Affiches Américaines of December 19, 1780. Issue no. 51, p.405.

(34) David D. Geggus. "Les esclaves de la plaine du Nord à la veille de la Révolution française, pt. 3" in: Revue de la Société haïtienne d'histoire et de géographie, Issues 142-149. Port-au-Prince, 1984. pp.15-44.

(35) Ellen Tarry. The other Toussaint : a modern biography of Pierre Toussaint, a post-revolutionary Black. Boston, 1981. p.206.

(36) Hannah Farnham Sawyer Lee. Memoir of Pierre Toussaint, born a slave in St. Domingo. Boston, 1854. p.27.

(37) Arthur Jones. Pierre Toussaint : A Biography. New York, 2003. p.97.

(38) Almanach royal d'Hayti pour l'année 1816", P. Roux, Imprimeur du Roi. Cap-Henry, 1816. pp.30, 53.

(39) Baron Pompée-Valentin de Vastey. Essai sur les causes de la revolution et des guerres civiles d'Hayti, faisant suite aux reflexions politiques sur quelques ouvrages et journaux francais, concernant Hayti avec differentes pieces. Sans-Souci, 1819. p.160.

(35) Ellen Tarry. The other Toussaint : a modern biography of Pierre Toussaint, a post-revolutionary Black. Boston, 1981. p.206.

(36) Hannah Farnham Sawyer Lee. Memoir of Pierre Toussaint, born a slave in St. Domingo. Boston, 1854. p.27.

(37) Arthur Jones. Pierre Toussaint : A Biography. New York, 2003. p.97.

(38) Almanach royal d'Hayti pour l'année 1816", P. Roux, Imprimeur du Roi. Cap-Henry, 1816. pp.30, 53.

(39) Baron Pompée-Valentin de Vastey. Essai sur les causes de la revolution et des guerres civiles d'Hayti, faisant suite aux reflexions politiques sur quelques ouvrages et journaux francais, concernant Hayti avec differentes pieces. Sans-Souci, 1819. p.160.

(40) Les Affiches Américaines of June 13, 1780. Issue no.24, p.190.

(41) C. N. Céligny Ardouin. Études sur l'histoire d'Haïti, Volume 1, Paris, 1853. p228.

(42) Les Affiches Américaines of December 31, 1766. Issue no. 53, p.442.

(41) C. N. Céligny Ardouin. Études sur l'histoire d'Haïti, Volume 1, Paris, 1853. p228.

(42) Les Affiches Américaines of December 31, 1766. Issue no. 53, p.442.

(43) Les Affiches Américaines of July 17, 1767. Issue no. 28, p.224.

(44) Les Affiches Américaines of August 7, 1781. Issue no.32, p.299.

(45) Les Affiches Américaines of June 23, 1784. Issue no.25, p.399.

(46) Les Affiches Américaines of February 23, 1788. Issue no.8, p.337.

(47) Les Affiches Américaines of December 17, 1786. Issue no.52, p.600.

(48) FR ANOM COL E 26 ; URL : ark:/61561/up424dxzw4m

(49) Roglo. Jean François Bérard ; URL : http://roglo.eu/roglo?lang=en;p=jean+francois;n=berard;

(50-52) Paul-Henri Gaschignard. " Gabriel Jean Baptiste Désiré NICOLAS" in : GHC (Généalogie et Histoire de la Caraïbe). No.238. pp.6374-6375 ; URL : https://www.ghcaraibe.org/bul/ghc238/p6374.rtf ; https://www.ghcaraibe.org/bul/ghc238/p6375.rtf

(53) France. Extrait des Minutes de la Chancellerie du Commissaire de France à New York. No. 633. in : NYPL (New York Public Library). Freedom certificate of Pierre Toussaint. URL : https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/8a1d4ef8-2bf0-95fe-e040-e00a1806794b

(54) Thomas J. Shelley. "Black and catholic in nineteenth century New York city : the case of Pierre Toussaint" in : Records of the American Catholic Historical Society of Philadelphia. Vol. 102, No. 4 (WINTER, 1991), pp. 1-17. (p.6)

(55) Hannah Farnham Sawyer Lee. Memoir of Pierre Toussaint... Op. Cit. p.5.

(56) Arthur Jones. Pierre Toussaint... Op. Cit. p.6.

(57) Arthur T. Sheehan, Elizabeth Odell Sheehan. Pierre Toussaint : a citizen of old New York. 1955. p.125.

(58) Eric Verkimpe. Geneanet.org. ; URL : https://gw.geneanet.org/verkimpe?lang=en&p=elizabeth&n=audige

(59) Eric Verkimpe. Geneanet.org. ; URL : https://gw.geneanet.org/verkimpe?lang=en&p=marie+louise+gabrielle&n=magnan

(60) Arthur Jones. Pierre Toussaint... Op. Cit. pp.315-316

(61) Arthur T. Sheehan, Elizabeth Odell Sheehan. Op. Cit. pp.9-10.

(62) Thomas J. Shelley. Op. Cit.

(63) Hannah Farnham Sawyer Lee. Op. Cit.

(64) Bishop Norbert Dorsey, CP. Pierre Toussaint of New York : Slave and Freedman. New York, 2014. p.13.

(65) David H. Brown. Santeria Enthroned: Art, Ritual, and Innovation in an Afro-Cuban Religion. Chicago, 2003. pp. 64-71, 317.

(49) Roglo. Jean François Bérard ; URL : http://roglo.eu/roglo?lang=en;p=jean+francois;n=berard;

(50-52) Paul-Henri Gaschignard. " Gabriel Jean Baptiste Désiré NICOLAS" in : GHC (Généalogie et Histoire de la Caraïbe). No.238. pp.6374-6375 ; URL : https://www.ghcaraibe.org/bul/ghc238/p6374.rtf ; https://www.ghcaraibe.org/bul/ghc238/p6375.rtf

(53) France. Extrait des Minutes de la Chancellerie du Commissaire de France à New York. No. 633. in : NYPL (New York Public Library). Freedom certificate of Pierre Toussaint. URL : https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/8a1d4ef8-2bf0-95fe-e040-e00a1806794b

(54) Thomas J. Shelley. "Black and catholic in nineteenth century New York city : the case of Pierre Toussaint" in : Records of the American Catholic Historical Society of Philadelphia. Vol. 102, No. 4 (WINTER, 1991), pp. 1-17. (p.6)