Home

Author : Rodney Salnave

Function : Dougan (Scribe)

Date : January 22, 2019

(Updated : Feb. 13, 2020)

The historical and religious genocide that Haiti is currently facing knows no bounds. In their quest to empty Haiti of its Revolution and its glorious memory, the genocidal revisionists will stop at nothing. Systematically, any valuable element belonging to the Haitian people is :

a) Polydor

This is why the revisionist Diouf talks about Yaya, while not mentioning that long before Yaya's exploits, the Trou du Nord and Terrier Rouge regions possessed a much more deadly maroon leader by the name of Polidor :

b) Thélémaque aka Canga

The Northeast in general, including the Le Trou area, that of Terrier Rouge, and other dependencies of Fort Dauphin (Fort Liberté), produced other maroon leaders. After Polidor, the most notable leader being Thélémaque aka Canga* :

a) Marie Yaya

As early as 1726, just a few decades since the start of captive (slave) importation to Saint Domingue, Marie Yaya, a captive (slave) from Petit Goave was condemned for having frequented thieves and murderers, and having shared the benefits of their crimes :

In 1781, a runaway ad mentions Yaya aka Jean Baptiste :

c) Jean-Pierre Yaya

In 1786, two ads were issued for the same fugitive named Yaya belonging to the settler Fauconet. The first ad, referring only to the name Yaya, is dated January 25 :

In 1788, the November 11th inventory for a coffee plantation located in Montrouis (in Artibonite region), owned by Jean Paqué (Count Delugé), reveals a Creole named Anne Yaya :

These 3 or 4 Yaya (2 or 3 men and 1 woman) were Creoles. That is, they were born in the christian-faithed Americas, which diminishes in a gigantic way the possibility that they were of muslim faith.

e) Marie-Françoise Yaya

Finally, we must take into account that "Yaya" was also the surnames of Saint Domingue colonists. This notice of 1793, mentions the departure of Marie-Françoise Yaya, a citizen of Fort Dauphin (actual Fort Liberté) who sought exile in New England :

a) Jean-Baptiste Yaya

Surprisingly, in 1814, in the ranks of the Royal Army of (Northern) Haiti, in the 30th Regiment of Sans-Souci, we found a lieutenant named Jean-Baptiste Yaya :

b) Caminère aka Yaya

On April 6, 1851, Port-au-Prince newspapers raised the name Caminère aka Yaya, during a trial concerning a conspiracy against the Soulouque government :

c) Sanilia aka Yaya

What is however obvious is that in Haiti, the name Yaya is not associated with islam at all. It remains a surname or an ordinary nickname. For example, a 1974 field report draws this profile of a traditionalist by the name of Sanilia, her nickname is Yaya :

d) Yaya, folk name

It is hardly surprising that we have not, so far, found a connection between islam and the Yaya name or nickname. Because, in Haitian culture, which derives directly from the experience lived in the Saint Domingue colony, the name Yaya first refers to a character of a tale. In this popular tale titled "Yaya, Ti Roro et Banda" (Yaya, Ti Roro and Banda), Yaya is the father of Ti Roro and the owner of Banda, the donkey. And nothing in this children's tale refers to religion or to islam.

Implicitly, Haitian culture also conceives Yaya as the nickname of a sleeping baby. Several songs exhibit this understanding. For example, in his song "Neuf heures et demie" (Anasilya, 1986), the legendary musician Ti Paris sings : Li lè pou l fè Yaya dodo. Dodo Yaya. Dodo cheri. That is to say, "It's time for him to make Yaya sleep. Sleep, Yaya. Sleep, darling." Another song, folk, this time, is titled : Ti Yaya nou pa bezwen kriye. (Mimi Barthélémy. Dis moi des chansons d'Haïti. Paris, 2007. p.11.) This amounts to saying : "Little Yaya, do not cry".

Then, without a doubt, the most widespread reference to Yaya is found in the folk song Balanse Yaya, that is to say, literally, "Swing Yaya". But in the context of the sleeping baby, "Rock Yaya".

Source : Mimi Barthélémy. Dis moi des Chansons d'Haïti : Chansons Traditionnelles illustrées par des peintures d'artistes haïtiens chantées et racontées pour les enfants. Paris, 2007. p.34.

In the Haitian lullaby "Balanse Yaya" is spread a list of goods that the parent promises to Yaya, her sleeping baby. Among these listed goods, one finds in particular a "beautiful pig" and a "beautiful prayer" which are "for Yaya". The association of the pig (an element banned in islam) to a prayer would be highly blasphemous in an islamic context. However, these two elements, incompatible according to the muslim doctrine, are nevertheless related to the name Yaya. This expresses how much the Haitian culture is foreign to the Mahometan universe.

Moreover, the fact that a pig is here described as "beautiful" goes against not only islam, but against the entire Abrahamic vision shared by islam, christianity and judaism. This lullaby, however, fits perfectly into the traditionalist sphere of thinking. And so does Yaya, the Haitian name or folk nickname.

And very often, this song "Balanse Yaya" accompanies a traditional game in which the players each move a small stone to the rhythm of the music ; in the manner of a musical chair game. This is significant, since in Haitian Creole, Yaya is also a verb. The Creole expression "Yaya kò", means "to move one's body", "to move", "to dance" (Transl.) (20) or to undertake physical activities of the same kind.

The Saint Domingue archives do not allow us to answer this question, since all the captives (slaves) going by the name of Yaya hitherto met were Creoles ; thus born in the island, or at least in the Americas. Fortunately, the www.slavevoyages.org database offers us an alternative. But this alternative is far from perfect. It only offers names of captives (slaves) destined for settlements other than Saint Domingue. And moreover, the names of these captives (slaves) were collected several years after the independence of Haiti (January 1, 1804).

Here, however, are the profiles of the captives (slaves) recorded as Yaya on their database. These are captives (slaves) that the ships carrying them illegally were confiscated at sea by the international court of the time :

Sources : http://www.slavevoyages.org/resources/names-database

From this list of captives (slaves) called Yaya, we gather from the outset that Yaya is not an Arabic name. The embarkation sites reveal that it is a pre-islamic "African" name prevalent both in the Western and the Central parts of the continent. Moreover, from 1812 to 1847, on this list, only 4 of the 12 captives bearing the name of Yaya were islamic adherents.** That is to say only one-third. And the islamized came from 2 boarding points : a) from Lagos, Onim, located in present-day Nigeria ; and then b) from the Bight of Benin, hence in present-day Benin.

So, let's check if these islamized Yaya would have belonged to this religion a few decades prior, at the time of the colony of Saint Domingue.

a) Yaya and the Bissago ethnic group

Two of the 11 captives (slaves), named Yayah, boarded the same ship from Gallinhas. This is one of Bissago Islands belonging to Guinea Bissau :

b) Yaya and the Congo tradition

The spiritual/folk dance titled "Yaya Ti Kongo" evokes a Congo link to the Yaya name. Likewise, Divinities within the various rites that hail from the Congo region bear this name. We can cite for example, the following Lwa or Jany : Yaya, Manbo Yaya, Yaya Poungwe, Simbi Yaya, Lawouye Simbi Yaya, Ti Yaya Toto, etc.

This sacred song of the traditional religion mentions Yaya :

Translation :

However, although it may serve as a nickname, this Yaya is not really a proper name. It derives from the Kikongo language in which Yaya means grandmother (big brother or big sister, in Lingala) :

Having failed to locate this Yaya people in Western "Africa", the closest name we've tracked down is the Munyo Yaya people of Kenya. The Munyo Yaya, mainly from the Tana River District, but initially from Ethiopia, were long-time traditionalists. Were they the group identified as Yaya in Saint Domingue? We cannot say for sure. However, the Munyo Yaya long served as captives to the Galla people. So, their sales in the East-"African" slave circuit, and their subsequent shipment to Saint Domingue is very possible. Because exchanges existed between the greater Korokoro region and the Arab and Swahili slave intermediaries. (35)

Moreover, Kenya's Kamba or Akamba ethnic group was found in Saint Domingue*** :

a) Mozambique

Saint Domingue newspapers are full of ads highlighting captives (slaves) from Mozambique. They were generally referred to by the generic name of "Mozambique" :

b) Tanzanie

In the Domingois colony, one sometimes comes across the Macondé ethnic group, hailing mainly from Tanzania, and to a lesser extent from Mozambique and Kenya :

c) Mayote

In Eastern "Africa", in the Indian Ocean, along the Mozambique Channel swarms with islands. Saint Domingue, the voracious, feeds there as well; especially in Mayotte, known as Mayoute :

d) Madagascar

And many of these captives (slaves) were from Madagascar, the big island bathing in the Indian Ocean, off East "Africa". In Saint Domingue, they were classified either under the banner "Madagascar", or as members of the Malgache, Malgasse, or Malagasse nation :

e) Ethiopia

We cannot fail to mention this renowned freed captive (slave) from Ethiopia. Marthe Adélaïde Modeste Testas, nicknamed Modeste Testas or Pelagie, was born in 1765 in Adele (Adele Keke, in the region of Arari located on the Ethiopian-Somali border). She was the maternal grandmother of François-Denys Légitime, former interim president of Haiti (December 18, 1888 - August 22, 1889).

Source : http://www.raphaeladjobi.com/archives/2019/06/05/37405338.html

At birth, Modeste Testas was given the name of Oriol-Poci or Alpouci. As a teenager, she was kidnapped by a member of another ethnic group seeking revenge on her father who embarked on a pilgrimage. Sold into slavery by her captor, she first transited through Bordeaux in France. Then she landed in Port-au-Prince where she was bought by François Testas who made her his companion. She was then taken to Jérémie, in Southeastern Saint Domingue.

Source : François-Deny Légitime. Histoire du gouvernement du général Légitime, Président de la République d'Haïti. Paris, 1890.

After being freed at the death of François Testas in July 1795, Modeste Testas or Pélagie paired up with Joseph Lespérance, who was also freed by the same master. They had several children, including Antoinette "Tinette" Lespérance, the mother of President Légitime. (47)

Source : Andre F. Chevallier. "Président Légitime" In : Aya Bombé! Revue mensuel. No.8. Port-au-Prince, Mai 1947. p.8.

[OTHER ARTICLES]

|

||

Function : Dougan (Scribe)

Date : January 22, 2019

(Updated : Feb. 13, 2020)

The historical and religious genocide that Haiti is currently facing knows no bounds. In their quest to empty Haiti of its Revolution and its glorious memory, the genocidal revisionists will stop at nothing. Systematically, any valuable element belonging to the Haitian people is :

- either attributed to islam,

- either attributed to the long-decimated Taino Indian culture,

- or either attributed to the Right of Men values of the French Revolution, against which, however, the Saint Domingue (Haitian) revolutionaries, traditionally and politically mobilized by royalist fervor, were openly opposed.

1- The islamic revision of Yaya

Gillot aka Yaya was a fugitive (or maroon) rebel leader from the Trou du Nord and Terrier Rouge localities, located north-east of the French colony of Saint Domingue (now Haiti). In punishment for his murderous misdeeds, he was executed in 1787, barely four years before the outbreak of the Haitian Revolution :"Au mois de septembre 1787, Gillot, surnommé Yaya, a été condamné au dernier supplice, pour avoir renouvelé, dans les paroisses du Trou et du Terrier Rouge, les scènes qui caractérisent un brigand sanguinaire." (1)Translation :

"In September 1787, Gillot, nicknamed Yaya, was sentenced to death, for having renewed, in the parishes of Trou du Nord and Terrier Rouge, the scenes that characterize a bloodthirsty brigand."Unsurprisingly, the islamic revisionist Sylviane Diouf sought to appropriate this Dominguois leader :

"What the French did not realize was that their most profitable colony, Saint Domingue, was fecund ground for Muslim maroons and rebels. The island had always had numerous maroon communities, (...) It is not known if some maroon communities were entirely composed of Muslims, but major communities had Muslim leaders. Yaya, also called Gillot, was a devastating presence in the parishes of Trou and Terrier Rouge, before he was executed in September 1787." (2)Diouf claims, shamelessly, that "it is not known if some maroon communities were entirely composed of Muslims, but major communities had Muslim leaders". But where are the proofs of that? For nothing in the Saint Domingue archives alluded to the moslem religion among the maroons, nor as a subversive element overall in the colony. Colonel Malenfant, a Saint Domingue colonist who looked for traces of islamized captives (slaves) in Saint Domingue, never met any personally. He then settle for verbal confirmations from other settlers who once possessed such captives (slaves) :

"Il y a des colons qui m'ont assuré qu'ils avaient eu pour esclaves des noirs mahométants [musulmans], et même des derviches." (3)Translation :

"There are settlers who have assured me that in the past, they had enslaved black mahometans [moslems], and even dervishes."Faced with scarcity, to reinforce his argument of the existence of muslim captives (slaves) in Saint Domingue, Malenfant had no choice but to rely on contacts he had with muslim entities elsewhere than in Saint Domingue. This reveals that the imposing and leadership muslim presence advanced by Diouf is false. It does not reflect the reality as experienced in Saint Domingue where the muslim element evoked only vague and distant memories from a handful of settlers. Moreover, the evidence suggests the contrary, since the settlers themselves tied murderous marronnage to the Congo (who are fundamentally traditionalists) :

"On a la preuve dans l'établissement des montagnes de l'acul de Samedi et par conséquent de Vallière. Tous les noms de piton des Nègres, de piton des Flambeaux, de piton des Ténèbres, de crête à Congo, rappellent des époques où des fugitifs se cantonnaient dans des points presque inaccessibles, ne fût-ce que par le défaut de chemins. On se rappelle encore de Polidor et de sa bande, de ses meurtres, de ses brigandages et surtout de la peine qu'on eut à l'arrêter." (4)Translation :

"There is evidence in the establishment of the l'acul de Samedi mountains and therefore of Vallière. All the names of piton des Nègres [Negroes peak], piton des Flambeaux [peak of Torches], piton des Ténèbres [peak of Darkness], crête à Congo [Congo crest], recall times when fugitives confined themselves to points that were almost inaccessible, if only because of the lack of roads. We still remember Polidor and his gang, his murders, his robberies, and above all the trouble we had to arrest him."In other words, the colonists linked the Congo ethnic group to the murderous maroons hidden in mountainous Acul de Samedi and Vallière, regions close to where Yaya operated. And they made no mention of nonexistent muslim maroons. So, on this aspect alone, Diouf's islamic statement is not credible.

1.1- Yaya wasn't his region's first rebel leader

The revisionists, in their quest to fabricate an islamic influence in the Saint Domingue colony, often proceed in a selective manner. They disregard the existence of a vast number of revolutionary leaders, in order to present only individuals whom they consider muslim or islamized.a) Polydor

This is why the revisionist Diouf talks about Yaya, while not mentioning that long before Yaya's exploits, the Trou du Nord and Terrier Rouge regions possessed a much more deadly maroon leader by the name of Polidor :

"La conformation de ces montagnes et de celles des autres paroisses contiguës, (...) tout dispose ces lieux pour être l'asile préféré des nègres fugitifs, qui peuvent choisir ou d'une vie fainéante, difficile à troubler, ou d'un plan de désolation pour les différentes parties exposées à leurs irruptions, sauf à payer de leur vie les crimes qu'ils entassent.Translation :

C'est une résolution du dernier genre que la dépendance du Trou à dû les longues vexations que lui fit le nègre Polydor à la tête d'une bande de nègres armés, qui fut enfin détruire par la réunion des habitants du lieu et des environs. L'effroi qu'avait répandu Polydor par ses atrocités était si grand, que sa destruction fut considérée comme un service rendu à toute la colonie; et le nègre Laurent, dit César, qui concourut, avec M. Nautel, son maître, à arrêter ce scélérat dans la savane qui a gardé son nom, où il fut tué, obtint des administrateurs, le 28 juin 1734, la liberté qu'ils avaient promise à l'esclave qui prendrait Polydor, mort ou vif." (5)

"The conformation of these mountains and those of the other contiguous parishes, (...) everything arranges these places to be the preferred asylum of the fugitive negroes, who can choose either a slack life, difficult to disturb, or a desolation plan for the various parties exposed to their irruption, except to pay with their lives the crimes they piled up.Here is a judgment rewarding those who neutralized Polydor and Joseph, his second in command :

It is a resolution of the latter kind that the dependence of Le Trou was due to the long vexations that the negro Polydor caused it at the head of an armed Negro band, who was finally destroyed by the meeting of the inhabitants of the place and the surroundings. The horror spread by Polydor's atrocities was so great that his destruction was considered a service to the whole colony; and the Negro Laurent, aka César, who concurred with M. Nautel, his master, to arrest this scoundrel in the savannah which has kept his name, where he was killed, obtained from the administrators, on June 28, 1734, the freedom which they promised the slave who would capture Polydor, dead or alive."

"JUDGMENT of Le Cap's Town Council, which grants to five Whites, employed on the Carbon estate, in Bois de Lance, a sum of 1000 pounds to be taken from the executed Rights Fund, for destroying a band of Maroon-Negroes, whose chiefs are Polydor and Joseph.And the complicity of a local slave facilitated the assassination of Polydor and his band. This slave has received his freedom as a reward for his treachery towards his comrades :

On June 10, 1734." (Transl.) (6)

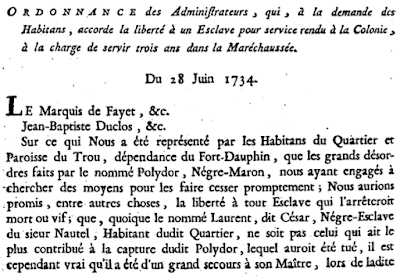

"ORDER of the Administrators, whom, at the request of the Inhabitants, grants freedom to a Slave for service rendered to the Colony, to serve three years in the Marechaussée [local police].So, contrary to Diouf's speculative assertion that there were islamized captives (slaves) among the Maroon bands, and that their leaders were of that religion, nothing related to Polydor, Joseph and the Trou du Nord maroon band ever referred to islam. Not their names, nor their practices.

On June 28, 1734.The Marquis de Fayet, etc.

Jean-Baptiste Duclos, etc.

On what has been represented to us by the inhabitants of the District and Parish of Le Trou, dependence of the Fort Dauphin, that the great disorders made by the so-called Polydor, Maroon-Negro, having engaged us to seek means to make them stop promptly ; We would have promised, among other things, freedom to any slave who would arrest him dead or alive; that although the so-called Laurent, aka César, Negro-Slave of Sieur Nautel, resident of the said District, is not the one who contributed the most to the capture of the said Polydor, whom would have been killed, it is however true that he was a great help to his Master, during the said capture..." (Transl.) (7)

b) Thélémaque aka Canga

The Northeast in general, including the Le Trou area, that of Terrier Rouge, and other dependencies of Fort Dauphin (Fort Liberté), produced other maroon leaders. After Polidor, the most notable leader being Thélémaque aka Canga* :

"Depuis et en 1777, le nègre Canga, autre chef de bande et désolateur du canton des Écrevisses, a expié sous le glaive de la loi, de nouveaux ravages..." (8)Translation :

"Since and in 1777, the negro Canga, another band leader and desolator of the Écrevisses canton, has expiated under the sword of the law, new ravages..."Voici l'arrêt de condamnation de Thélémaque dit Canga au 2 octobre 1777 :

"Le Cap's Town Council judgment, which condemns the so-called THÉLÉMAQUE, aka Canga, Negro slave, band Leader of maroon Negroes, convinced to have ravaged, at the head of the said armed band, several Houses of Écrevisses and Fonds-bleus, and to have defended himself against a white man ; the so-called ISAAC, also a Negro slave, second chief of the band, convinced of the same facts ; and the so-called PIRRHUS, aka Candide, also Negro slave of the band, convinced of having injured a white, to be broken alive, to expire on the wheel, to have their heads set on pickets in the main road from Fort Dauphin to Écrevisses ; six other Negroes and Negresses to be hanged, others to be whipped and branded ; the judgment to be printed, published and posted, both in Le Cap and Fort Dauphin.Canga, as in Thélémaque Canga, displays a Congo consonance. This corresponds to all the fugitives of this name found in the Saint Domingue archives :

On October 2, 1777." (Transl.) (9)

"On the 4th, Canga, Congo, without branding, 24 years old, 4 feet 10 inches tall, marked with smallpox, claiming to belong to Mr. Claicheboscau, in Kingston." (Transl.) (10)And it was only 10 years after the death of Thélémaque Canga, who was band leader in the region, that Gillot aka Yaya suffered the same fate. Thus, without taking away from Gillot aka Yaya's efforts and ultimate sacrifice in the struggle for his people's liberation, the facts show that he was part of a resistance (Congo and traditionalist in flavor) that preceded him by several decades in the region. Besides, settler Moreau de Saint Méry pointed out that Yaya simply "renewed" the murderous scenes in the area.

2- The name Yaya in the Saint Domingue colony

Before proposing that a captive (slave) is of muslim faith or otherwise, tangible evidence must demonstrate that. The revisionists having failed this task, let's look for them what the archived data say about Yaya as a name.a) Marie Yaya

As early as 1726, just a few decades since the start of captive (slave) importation to Saint Domingue, Marie Yaya, a captive (slave) from Petit Goave was condemned for having frequented thieves and murderers, and having shared the benefits of their crimes :

"JUDGMENT by the Petit Goave Council, against several thieves slaves and murderers, which puts a bounty on the heads of several others.

b) Yaya aka Jean BaptisteOn May 6, 1726.Between the Substitute of the Attorney General of the King at the Royal Seat of that City, Plaintiff and Accused, Appellant of the Sentence delivered to the said Seat, on the eleventh of last April; Against Thirty Negroes, Negresses and Mulatto women, Slaves, Respondents.(...)Declares Marie Goyo, Slave, Marie Yaya and Madeleine, Negresses, well attained and convinced to have frequented and removed the so-called Forban, La Rose and Bernard, to have had a trade with them, and to have received various stolen effects, which is mentioned at the trial ; for compensation of what, condemns them to be hanged and strangled until death ensues." (Transl.) (11)

In 1781, a runaway ad mentions Yaya aka Jean Baptiste :

"A negro named Yaya, aka Jean-Baptiste, creole of Martinique, very robust, stamped DANEY, gone maroon for ten days. Those who will recognize him, are asked to arrest him and give notice to Mr. Daney, Trader in Le Cap, to whom he belongs." (Transl.) (12)

c) Jean-Pierre Yaya

In 1786, two ads were issued for the same fugitive named Yaya belonging to the settler Fauconet. The first ad, referring only to the name Yaya, is dated January 25 :

"Yaya, size 5 feet 4 inches, stamped FAUCONET, has a burn on the right hand, maroon. Give notice to M. Fauconet." (Transl.) (13)The second ad published May 24, revealed that Jean-Pierre Yaya was the real name of this fugitive, said to be a good tailor :

"A Creole Negro, good tailor, saying that he is free, taking various names, speaking good French, aged 22, sized 5 feet 5 inches, stamped on the right breast FAUCONET, reddish skin, missing both teeth in the upper jaw, on the front. ; has a burn on the right hand, and a scar on the right shoulder-blade, very slight and slender, with large feet and very thick lips, has been maroon for four months. The name of the said negro is Jean-Pierre Yaya. Those who are acquainted with him are requested to give notice to M. Fauconet, rue de Conflans et du Vieux Gouvernement, or Messrs. Comard and Bancheraux, merchants in Le Cap." (Transl.) (14)d) Anne Yaya

In 1788, the November 11th inventory for a coffee plantation located in Montrouis (in Artibonite region), owned by Jean Paqué (Count Delugé), reveals a Creole named Anne Yaya :

"Anne Yaya, Creole, aged 31, maid. . 4.500

Agathe, Colocoly, aged 39, maid. . . . 3.000

Acanotte, Aguia, aged 41, maid. . . . . 2.500

Junon, Arada, aged 48, maid. . . . . . . 1.000." (Transl.) (15)

e) Marie-Françoise Yaya

Finally, we must take into account that "Yaya" was also the surnames of Saint Domingue colonists. This notice of 1793, mentions the departure of Marie-Françoise Yaya, a citizen of Fort Dauphin (actual Fort Liberté) who sought exile in New England :

(...)

"DEPARTURES FOR NEW-ENGLAND.And when we take into account that very often, the captives (slaves) obtained (or adopted) their owners' names, the name "Yaya" loses the exclusivity of an "African" origin. And without this "African" exclusivity, the islamic revisionist thesis falls flat.

THE CITIZENS,

(...)Barrousel, Duboulet, Parouneau, Gaillard, and the citizen Marie-Françoise Yaya ; all from Fort-Dauphin." (Transl.) (16)

3- The name Yaya in Haiti

The use of Yaya as a surname or as a nickname carried on in the independent state of Haiti. Let's take a look at this aspect.a) Jean-Baptiste Yaya

Surprisingly, in 1814, in the ranks of the Royal Army of (Northern) Haiti, in the 30th Regiment of Sans-Souci, we found a lieutenant named Jean-Baptiste Yaya :

"30th Regiment of Sans-SouciWas it the same Yaya who was a fugitive 33 years prior? Highly possible. But anyway, Lieutenant Yaya has kept the christian name "Jean-Baptiste". So he did not opt for a muslim name as a free person in 1814. Was he ever a muslim? We aren't able to say.

Staff Major, Gentlemen,

de Benoit Rau, colonel, C.

de Lejeune, lieutenant colonel, C.

Félix Jean, idem.

Jean Pierre, idem.

Dieudonné Lafleur, second lieutenant, quartermaster.

Pierre Louis Charlot, captain, instructor.

Saint Antoine, capitaine, adjudant major.

Jean-Baptiste Yaya, lieutenant, idem.

Saty, second lieutenant, idem." (Transl.) (17)

b) Caminère aka Yaya

On April 6, 1851, Port-au-Prince newspapers raised the name Caminère aka Yaya, during a trial concerning a conspiracy against the Soulouque government :

"Frédéric aîné, in his confrontation with Cazeau denies these facts ; however it remains clear that he was aware of this manifesto's circulation by the revelation given to him by Senator Clervau and his brother Caminère aka Yaya — on Saturday night, the day before his arrest." (Transl.) (18)Brother of a senator named Clervau, also informed of the plot, Caminère aka Yaya should be a Creole (born in the island). Consequently, there is strong doubt that his nickname Yaya had any connection with a particular religion. And even less of a link with the islamic religion, which was probably not transferred to the Creole generation ; that is, when islam was there to be found.

c) Sanilia aka Yaya

What is however obvious is that in Haiti, the name Yaya is not associated with islam at all. It remains a surname or an ordinary nickname. For example, a 1974 field report draws this profile of a traditionalist by the name of Sanilia, her nickname is Yaya :

"First name : Sanilia.No one will confuse Sanilia, nicknamed Yaya, this fervent traditionalist and strong alcohol seller, with a muslim woman.

– Nickname : Yaya.

– Age : 32.

– Sex : Female.

– Profession : Merchant of Clairin (raw rum harvested from the still).

– Home : Jacmel.

– Religion : Baptized catholic. Did not make her first communion, never go to church. - Houmfor [voodoo temple she goes to]: "I've been going since I was a baby, in the arms of my mother." - Kanzo [initiation stage]: Was initiated at the age of 28 by the "mambo" - Thémélise, She had to wait, for lack of money. - Why ?: "I often saw "loa" in my dreams and even "Erzulie Dantor" and "Saint James-the-Major"."

– Parents : Peasant father, marketplace merchant mother. Neither are "kanzo", but they serve the "loa".

– Brothers and sisters : Three sisters, all "kanzo". (...)

– Presence at the "houmfor" : Every day." (Transl.) (19)

d) Yaya, folk name

It is hardly surprising that we have not, so far, found a connection between islam and the Yaya name or nickname. Because, in Haitian culture, which derives directly from the experience lived in the Saint Domingue colony, the name Yaya first refers to a character of a tale. In this popular tale titled "Yaya, Ti Roro et Banda" (Yaya, Ti Roro and Banda), Yaya is the father of Ti Roro and the owner of Banda, the donkey. And nothing in this children's tale refers to religion or to islam.

Implicitly, Haitian culture also conceives Yaya as the nickname of a sleeping baby. Several songs exhibit this understanding. For example, in his song "Neuf heures et demie" (Anasilya, 1986), the legendary musician Ti Paris sings : Li lè pou l fè Yaya dodo. Dodo Yaya. Dodo cheri. That is to say, "It's time for him to make Yaya sleep. Sleep, Yaya. Sleep, darling." Another song, folk, this time, is titled : Ti Yaya nou pa bezwen kriye. (Mimi Barthélémy. Dis moi des chansons d'Haïti. Paris, 2007. p.11.) This amounts to saying : "Little Yaya, do not cry".

Then, without a doubt, the most widespread reference to Yaya is found in the folk song Balanse Yaya, that is to say, literally, "Swing Yaya". But in the context of the sleeping baby, "Rock Yaya".

Source : Mimi Barthélémy. Dis moi des Chansons d'Haïti : Chansons Traditionnelles illustrées par des peintures d'artistes haïtiens chantées et racontées pour les enfants. Paris, 2007. p.34.

In the Haitian lullaby "Balanse Yaya" is spread a list of goods that the parent promises to Yaya, her sleeping baby. Among these listed goods, one finds in particular a "beautiful pig" and a "beautiful prayer" which are "for Yaya". The association of the pig (an element banned in islam) to a prayer would be highly blasphemous in an islamic context. However, these two elements, incompatible according to the muslim doctrine, are nevertheless related to the name Yaya. This expresses how much the Haitian culture is foreign to the Mahometan universe.

Moreover, the fact that a pig is here described as "beautiful" goes against not only islam, but against the entire Abrahamic vision shared by islam, christianity and judaism. This lullaby, however, fits perfectly into the traditionalist sphere of thinking. And so does Yaya, the Haitian name or folk nickname.

And very often, this song "Balanse Yaya" accompanies a traditional game in which the players each move a small stone to the rhythm of the music ; in the manner of a musical chair game. This is significant, since in Haitian Creole, Yaya is also a verb. The Creole expression "Yaya kò", means "to move one's body", "to move", "to dance" (Transl.) (20) or to undertake physical activities of the same kind.

4- The name Yaya in the mother-continent

From which territory did the name Yaya come from? Revisionist Diouf bases her islamic claim on the popularity of Yaya as a first name among the populations of Western "Africa", today largely islamized. But what was the origin of Yaya at the time of the Saint Domingue colony?The Saint Domingue archives do not allow us to answer this question, since all the captives (slaves) going by the name of Yaya hitherto met were Creoles ; thus born in the island, or at least in the Americas. Fortunately, the www.slavevoyages.org database offers us an alternative. But this alternative is far from perfect. It only offers names of captives (slaves) destined for settlements other than Saint Domingue. And moreover, the names of these captives (slaves) were collected several years after the independence of Haiti (January 1, 1804).

Here, however, are the profiles of the captives (slaves) recorded as Yaya on their database. These are captives (slaves) that the ships carrying them illegally were confiscated at sea by the international court of the time :

Captives (slaves) called Yaya, origin,

destination, etc.

|

||||||||||

ID

|

Name

|

Age

|

Height [in]

|

Sex

|

Religion

|

Voyage ID

|

Ship name

|

Arrival

|

Embarkation

|

Disembarkation

|

5324

|

Yaya

|

13

|

57.0

|

Girl

|

islamized

|

2947

|

Bella Eliza

|

1824

|

Lagos, Onim

|

Freetown

|

9485

|

Yayah

|

23

|

63.0

|

Female

|

ancestral

|

2841

|

Lynx

|

1827

|

River Brass

|

Freetown

|

10621

|

Yahyah

|

18

|

58.0

|

Female

|

ancestral

|

2970

|

Dos Amigos

|

1827

|

Badagry

|

Freetown

|

15558

|

Yahya

|

9

|

47.0

|

Girl

|

ancestral

|

3015

|

Triumpho

|

1828

|

Anamabu

|

Freetown

|

23531

|

Yayah

|

24

|

61.0

|

Female

|

ancestral

|

2418

|

Maria

|

1831

|

Gallinhas

|

Freetown

|

23534

|

Yayah

|

16

|

60.0

|

Female

|

ancestral

|

2418

|

Maria

|

1831

|

Gallinhas

|

Freetown

|

29366

|

Yaya

|

11

|

56.0

|

Boy

|

islamized

|

2444

|

Tamega

|

1834

|

Lagos, Onim

|

Freetown

|

30933

|

Yahyah

|

20

|

61.0

|

Female

|

ancestral

|

3047

|

Antrevido

|

1835

|

Whydah

|

Freetown

|

35100

|

Yaya

|

10

|

49.0

|

Girl

|

islamized

|

3048

|

Thereza

|

1835

|

Lagos, Onim

|

Freetown

|

104040

|

Yaya

|

11

|

66.0

|

Boy

|

ancestral

|

7508

|

Andorinha

|

1812

|

West Central Africa

|

Freetown

|

104041

|

Yaya

|

11

|

53.75

|

Boy

|

ancestral

|

7508

|

Andorinha

|

1812

|

West Central Africa

|

Freetown

|

180656

|

Yayah

|

25

|

69.0

|

Male

|

islamized

|

3620

|

Telessro(a)

Tebessan

|

1847

|

Bight of Benin

|

Freetown

|

Sources : http://www.slavevoyages.org/resources/names-database

From this list of captives (slaves) called Yaya, we gather from the outset that Yaya is not an Arabic name. The embarkation sites reveal that it is a pre-islamic "African" name prevalent both in the Western and the Central parts of the continent. Moreover, from 1812 to 1847, on this list, only 4 of the 12 captives bearing the name of Yaya were islamic adherents.** That is to say only one-third. And the islamized came from 2 boarding points : a) from Lagos, Onim, located in present-day Nigeria ; and then b) from the Bight of Benin, hence in present-day Benin.

So, let's check if these islamized Yaya would have belonged to this religion a few decades prior, at the time of the colony of Saint Domingue.

a) The Gulf of Benin

One of the four islamized Yaya came from the Bight of Benin, a hotbed of traditional religion.

(Bight of Benin 1793)

Source : "Dahomy and its environs by R. Norris.", 1793. In : Archibald Dalzel. The history of Dahomy, an inland Kingdom of Africa. New York Public Library Digital Collection ; URL : http://digitalgallery.nypl.org/nypldigital/id?1107222

The Saint Domingue settlers share that assessment :

"According to the Arada negroes, who are the true followers of Vaudoux in the colony, and who maintain its principles and the rules... (...) It is very natural to believe that Vaudoux owes its origin to the snake cult, to which the inhabitants of Juida [Ouidah], are particularly devoted, and who say it originated from the kingdom of Ardra [said Arada or Rada in the Haitian ritual], from the same Slave Coast..." (Transl.) (21)Moreover, this captive of the name of Yaya in question boarded in 1847. Given the late exposure (post 1830) of the Gulf of Benin to an islamic presence of importance, the probability that such an individual would have been of moslem faith, during the time of the Saint Domingue colony (so before 1791) is very tiny :

"Hence, the presence of Islamic factor in the Bight of Benin can be traced most especially to the late eighteenth century, and at the ports of Porto Novo and Lagos, not Ouidah. In the last years of the trans-Atlantic slave trade from the 1830s, the Muslim presence was more pronounced, both as victims of the trade and merchants of the trade." (22)However, as slim as it may be, this possibility still remains for the port of Porto Novo (and that of Lagos, which we will see). So, that a captive (slave) was called Yaya in Saint Domingue did not guarantee that he was of muslim faith, as Diouf supposed. But, although it was more likely that this captive (slave) was traditionalist, the evidence also does not allow us to dismiss this islamic possibility with a brush of a stroke.

b) Lagos, Onim

The other 3 of the 4 islamized Yaya came from the Lagos harbor, a coastal area in southern Nigeria that was then populated mainly by Yoruba traditionalists.

(The Lagos Islands and the city of Badagry, in present-day Nigeria)

Source : https://www.google.com/maps/@6.541838,3.4281102,10z

But, in addition to its traditional Yoruba population, Lagos was home to a small amount of islamized Hausa slaves from northern Nigeria. And it is conceivable that, in the time of the Saint Domingue colony, some of them were sold, and among those, some may have carried the Yaya name. However, the so-called "islamic" practice of these Hausa was mixed with their traditional worship called Bori.

These Hausa traditionalists honoring the Bori, that is to say their ancestral Spirits, formed the majority of those targeted by slave captors. (23) They found themselves in large numbers in Saint Domingue. The traditional Haitian ritual retains from their ancestral cult (like that of the Fulani, their neighbors), the designation "horses" which applies to participants in Spirit possession. Since they are "ridden" momentarily by the spirits :

Moreover, this same list reveals that in 1827, a traditionalist woman by the name of Yaya boarded in Badagry. Badagry, this nearby city of Lagos, was populated by Yoruba people who brought to the traditional Haitian religion the Nago warrior rite, in the center of which is the Ogun cult, including Ogoun Badagri.

We can thus affirm that the majority of captives (slaves) called Yaya navigating towards the Americas, were traditionalists. For it was not until 1830 that the expansion of the islamic presence was considerable in the ports of southern Nigeria and the Gulf of Benin. This is reflected in the 3 of the 4 islamized captives (slaves) named Yaya who were shipped post 1830, that is to say in 1834, 1835 and 1847. Hence, let us analyze the other embarkation spots on this list and the links preserved in literature and the Haitian memory.

(Bori worship by the Hausa of Nigeria)

Source

: Christoph Henning, Klaus E. Müller, Ute Ritz-Müller. Afrique-La magie

dans l’âme : rites, charmes et sorcellerie. Könemann, 2000. p.284. These Hausa traditionalists honoring the Bori, that is to say their ancestral Spirits, formed the majority of those targeted by slave captors. (23) They found themselves in large numbers in Saint Domingue. The traditional Haitian ritual retains from their ancestral cult (like that of the Fulani, their neighbors), the designation "horses" which applies to participants in Spirit possession. Since they are "ridden" momentarily by the spirits :

"La danse se transforme en état de possession. La relation entre l'esprit et le médium est exprimée par l'image du "cheval" (le médium) et du "cavalier" (l'esprit). Les médiums masculins sont appelés doki ou étalon, les médiums féminins godiya ou jument." (24)Translation :

"The dance is transformed into a state of possession.The relationship between the mind and the medium is expressed by the image of the "horse" (the medium) and the "rider" (the spirit). The male mediums are called doki or stallion, the female godiya mediums or mare."This Hausa religious syncretism (a mixture of islam with the traditional religion) displeased Ousmane Dan Fodio, a muslim purist who, on February 21, 1804, launched a holy war or jihad against the Hausa of Gobir (in Northern Nigeria), which solidified the islamic cult among the Hausa nobles. But despite Dan Fodio's jihad that lasted several years, and the persecutions that followed, the Bori cult perseveres in Hausaland, particularly in rural areas :

"In reality, we do not really know how was constituted this muslim people who today claims itself of islamic origins but deeply anchored in the old animist culture.The fervor of the Bori tradition, still observed in the Hausa region, testifies that this people was more traditionalist at the time of their crossing to Saint Domingue, in 1791 at the latest. Because, at the start of Dan Fodio's jihad on February 21, 1804, Haiti was already independent on January 1 of that same year, and the slave trade inoperative there for more than 12 years.

(…)

The islamized population is still strongly influenced by traditional beliefs, and its social spectrum reflects the degree of islamic impregnation. Nobles, courtiers, administrators, craftsmen and, in general, city-dwellers affect a more or less strict observance, and distinguish themselves from the rural strata, consisting of free men and former captives. As in the Djerma of the Niger Valley, possession cults and maraboutism are practiced in many circumstances. The upper layers of society were strongly islamized after the holy war of the Fulani reformer Ousmane dan Fodio in the early nineteenth century." (Transl.) (25)

Moreover, this same list reveals that in 1827, a traditionalist woman by the name of Yaya boarded in Badagry. Badagry, this nearby city of Lagos, was populated by Yoruba people who brought to the traditional Haitian religion the Nago warrior rite, in the center of which is the Ogun cult, including Ogoun Badagri.

We can thus affirm that the majority of captives (slaves) called Yaya navigating towards the Americas, were traditionalists. For it was not until 1830 that the expansion of the islamic presence was considerable in the ports of southern Nigeria and the Gulf of Benin. This is reflected in the 3 of the 4 islamized captives (slaves) named Yaya who were shipped post 1830, that is to say in 1834, 1835 and 1847. Hence, let us analyze the other embarkation spots on this list and the links preserved in literature and the Haitian memory.

4.1- The name Yaya in the Haitian ritual

The name of 2 Yaya traditionalists is echoed in Haitian culture, namely : a) Yaya from the Bissago Islands ; and b) Yaya from the Congo.a) Yaya and the Bissago ethnic group

Two of the 11 captives (slaves), named Yayah, boarded the same ship from Gallinhas. This is one of Bissago Islands belonging to Guinea Bissau :

(Gallinhas and all the Bissago Islands in present-day Guinea-Bissau)

Source

: "Map of the sectors of the Bolama Region, Guinea-Bissau". URL :

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Galinhas#/media/File:Map_of_the_sectors_of_the_Bolama_Region,_Guinea-Bissau.png

Gallinhas, part of the Bissago Islands, is actually located in the Senegambian zone that had ancient and continuous contacts with islam. However, the inhabitants of the Bissago Islands are known to have rejected islamic conversion :

"Bissago ou Bijago (Iles). Archipel de la Guinée-Bissau comportant dix-huit iles (…) Les habitants, Bidjogo, opposèrent aussi bien une forte résistance aux Portugais qui découvrirent l'archipel en 1456 et qui s'établirent dans les comptoirs côtiers du continent. Ils refusèrent aussi bien le christianisme que l'islam ; aujourd'hui, 95% des 10000 habitants sont animistes. La société est structurée en clans matrilinéaires, avec une prêtresse pour l'entretien du feu sacré et la divination..." (26)

Translation :

"Bissago or Bijago (Islands). Guinea-Bissau archipelago with eighteen islands (...) The inhabitants, Bidjogo, also strongly resisted the Portuguese who discovered the archipelago in 1456 and settled in the counters. On the mainland, they refused both christianity and islam ; today, 95% of the 10,000 inhabitants are animists. Society is structured in matrilineal clans, with a priestess for the maintenance of sacred fire and divination."In Haiti, in 1837, was listed an "African" dance called "Yaya Bisango" :

"I will mention for example the most esteemed tunes, taken from these different dances: Sor Zabett Congo, Yaya Bisango, Amelinn, Mayemba, Imbimm oh! but the Creole connoisseur only has to hear one sound from these tunes, even if it was played for the first time, to immediately distinguish to which dance it belongs." (Transl.) (27)The existence of this dance called "Yaya Bisango" hides the fact that a very small amount of Bissago were brought in the Saint Domingue colony :

"Presque en face des Mandingues, et en tirant au Midi, sont les îles des Bissagots, dont la traite appartient aux Portugais. Il en vient fort rarement..." (28)Translation :

"Almost facing the Mandingoes, and leaning towards the South, are the Bissagots islands, of which the slave trade belongs to the Portuguese. And very rarely are they brought from there…"But yet, this Bissago people is highly notorious in Haiti. And this, not by virtue of any moslem faith, but rather according to their dreaded traditionalist and magical practices, organized and conveyed through the Bizango secret societies that they created on the island. And although traditionalists, these Bizango secret societies are apart from traditional Haitian religion. Because their practices, greatly feared, do not agree with the moral codes of the frank traditional religion. This stems from the unsavory behavior of the Bissagot ethnic group from its native land :

"The Bissagots are tall, strong and robust, but they only feed on shellfish, fish, palm oil and palm kernels, which they call chavaux. They sell millet, rice and legumes to Europeans. They have an extreme passion for alcohol, they consume a great deal, and this article is sold to them, very costly.So, if the rebel called Yaya came from the Bissagots archipelago, his sanguinary acts that were punished in Saint Domingue matched : 1) the way the Bissagot treat their enemies with cruelty ; 2) the manner which Haitian Bizango secret societies are reputed to act (rightly or wrongly). But, anyway, so far, no historical element allows one to specify the ethnicity of Gillot nicknamed Yaya.

The passion for alcohol is so strong in them that it makes them furious and distorted. As soon as a ship presents itself and sells this item, it is to whom will it be in greater quantity and will be more quickly served. The weaker then becomes the prey of the strongest. The father sells his children, and if the child can seize his father and mother, he takes them to the Europeans, sells them and swaps them for alcohol ; he then makes debauchery, and rejoices as long as the price of the authors of his days lasts.

All these people are idolatrous and naturally cruel ; they cut off the heads of the men they have killed, walk their bodies through the streets, skin them, dry their skin with their hair, and bear them in front of their houses, as a mark of their bravery and their victories." (Transl.) (29)

b) Yaya and the Congo tradition

The spiritual/folk dance titled "Yaya Ti Kongo" evokes a Congo link to the Yaya name. Likewise, Divinities within the various rites that hail from the Congo region bear this name. We can cite for example, the following Lwa or Jany : Yaya, Manbo Yaya, Yaya Poungwe, Simbi Yaya, Lawouye Simbi Yaya, Ti Yaya Toto, etc.

This sacred song of the traditional religion mentions Yaya :

Mwen salonge,

Yaya, n ap salonge

Yaya, n ap salonge

apre Bondye nan syèl

Translation :

I am (doing) salonge,

Yaya, we are (doing) salonge

Yaya, we are (doing) salonge

after the Good God in the sky

However, although it may serve as a nickname, this Yaya is not really a proper name. It derives from the Kikongo language in which Yaya means grandmother (big brother or big sister, in Lingala) :

"Yaya : 1) grand mère (f) ; 2) titre respectueux d'un oncle maternel, d'un aîné..." (30)Translation :

"Yaya: 1) grandmother (f) ; 2) respectful title to a maternal uncle, an elder..."And in Haitian Creole, Yaya similarly refers to a grandmother or an aunt :

"Yaya 1. n. prop. tante Yaya." (31)Translation :

"Yaya 1. f n. Aunt Yaya."It is therefore not trivial that this 1836 historical short story presented the following character of a grandmother named Yaya :

"Il ne restait plus de doute sur l'espèce de la maladie ; aussi n'était-il point de malédictions que la vieille Yaya ne proférât contre la secte infernale, dite cochon-sanspoil." (32)Translation :

"There was no longer any doubt as to the nature of the disease ; likewise there was no curse that old woman Yaya kept from spewing against the infernal sect, the so-called cochon-sanspoil [pig-without-hair]."Only 32 years post the independence of Haiti, yet a character named Yaya did not reflect the islamic portrait that revisionist Diouf pinned on the Yaya name. On the contrary, we are entirely immersed in a Haitian traditionalist and syncretic universe. To the Yaya name, author Ignace Nau associated a multitude of situations and keywords that always refer (rightly or wrongly) to the traditional and syncretic Haitian religion :

- Bondieu (name of the Creator, not Allah)

- Men carrying macoute [bags] (who are vaudoux)

- Papa loi (Name of great traditionalist officials)

- Mangé-marassa (offerings to the Twin Divinities)

- Caplata counselors (magicians)

- Traditional historical songs : "Cangay bafio té", "Hé! hé boumba houm!"

- Maldioc (magic protective) necklace

- Loup-garou (werewolf)

- So-called cochon-sanspoil (pig-without-hair) sect

- Holy water, incense and palm tree stalk blessed on twig day

- Rosary and pilgrimage to the altars of Higuey

- Etc.

5- The Yaya Nation in the Saint Domingue colony

In Saint Domingue, it often happens that the ethnicity of a captive (slave) serves as his name or nickname. Thus, the nickname Yaya could have been attributed to the rebel Gillot in reference to his ethnicity. However, there was also an ethnic group or Nation known as Yaya in Saint Domingue :"In Fort-Dauphin, at the 1st of the current [month], a new Negro, Yaya nation, stamped on the right breast BDF, arrested in Mont-Organisé, could not say his name or that of his master." (Transl.) (34)

Moreover, Kenya's Kamba or Akamba ethnic group was found in Saint Domingue*** :

"Augustin, Camba nation, 18 years old, 5 feet 2 inches tall, stamped VAIDIÉ, was brought back from the Spanish side." (Transl.) (36)In this same ad, the arrest of another captive (slave) belonging to the Macamba ethnic group was also reported :

"Sucemond, Macamba nation, stamped GDR, 24 years old, could not say his master's name, was brought back from the Spanish side." (Transl.) (37)Similarly, the nation called Oluou in Saint Domingue comes from Kenya. It is more specifically the Dholuo speaking Luo people.

5.1- Presence of captives (slaves) from Eastern "Africa"

But some will argue that Eastern "Africa", where Kenya is located, did not provide as many captives (slaves) to the Saint Domingue colony as did Western and Central "Africa". They will not be wrong. But, the arrival in Saint Domingue of captives (slaves) extirpated from East "Africa" is massively underestimated. The archives supply evidence of that.a) Mozambique

Saint Domingue newspapers are full of ads highlighting captives (slaves) from Mozambique. They were generally referred to by the generic name of "Mozambique" :

"At Port-au-Prince, the 2nd of this month, Zabel, Mozambique, stamped J GARNIER, below, AU CAP, has marks of his country on the face, unable to say the name of his master ; (…) on the 3rd, Jason, Mozambique, without stamp, has marks of his country on the face, claiming to belong to Mrs. Meynardie, Picard & Compagnie ; Pantin, Adrien, Laurent and Maurice, Mozambiques, stamped LOMO, claiming to belong to Mr. Lomo, in Saint-Marc." (Transl.) (38)Admittedly, we are witnessing the overrepresentation of captives (slaves) from Mozambique. Because, in proportion to their quantity, the "Mozambiques" were by far the most fervent partisans of escaping (or marronnage) on the island. But in Saint Domingue, one also spotted the Maquoua or Macoua nation that was classified under its true ethnic name :

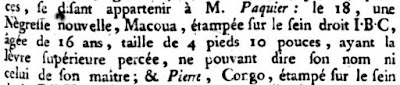

"On the 18th, a new Negress, Macoua, stamped on the right breast, I.B.B, aged 16, 4 feet 10 inches tall, with the pierced upper lip, unable to say her name or that of her master." (Transl.) (39)There was also an impressive number of fugitives from the so-called Kiamba, Quiamba or Quiembo nation in Saint Domingue. These were individuals captured in the Quirimbas Islands of Mozambique, as was the so-called Hibou (or sometimes Ybo, or even Ibo)**** nation that comes from the adjacent Ibo Island that served as a slave trading post. Similarly, the captives (slaves) rescued from Mozambique's Manica District formed the Maniga or Maninga nation in Saint Domingue. (40)

b) Tanzanie

In the Domingois colony, one sometimes comes across the Macondé ethnic group, hailing mainly from Tanzania, and to a lesser extent from Mozambique and Kenya :

"Jean-Pierre, Macondé, stamped, as much as one could distinguish it, DESHO & REGHIER, unable to say the name of his master." (Transl.) (41)The Saint Domingue settlers grouped a pleiad of ethnicities under the label "Mozambique", captives (slaves) among which, historian colonist Moreau de Saint Méry identified the Quiloi and the Montfiat. (42) We now know that the Quiloi nation comes from Tanzania's Kilwa Island. Also a Tanzanian island, the name Monfiat has however undergone several transformations over time. It became Mon fee, and nowadays, that Island is called Mafia. (43)

c) Mayote

In Eastern "Africa", in the Indian Ocean, along the Mozambique Channel swarms with islands. Saint Domingue, the voracious, feeds there as well; especially in Mayotte, known as Mayoute :

"On the 10th, Lafortune, Mayoute, stamped on the right breast ..., aged 29, 5 feet tall, has [mar]ks of his country on his cheeks, and has received a shot [from a] rifle, claims to belong to Mrs. widow Gentille, Resid[ing] in Petit-Trou." (Transl.) (44)It should be noted that the word Mayoute is perpetuated in the traditional Haitian religion, especially through sacred songs. The word Mayotte, properly speaking, is found in Lamayòt (La Mayotte), the name of a masked character that plays a catalytic role in Haitian carnival parades. (45)

d) Madagascar

And many of these captives (slaves) were from Madagascar, the big island bathing in the Indian Ocean, off East "Africa". In Saint Domingue, they were classified either under the banner "Madagascar", or as members of the Malgache, Malgasse, or Malagasse nation :

"Zéphir, of a very light color, capable of being mistaken for a Mulatto, without stamp, of Malgache nation, of the height of 5 feet 1 inch or so, has an haggard look, thick hair, very high shoulders, Indian accent, and very marked, belonging to Mr. Cornu, marooned from Le Cap on the 17th of the current [month] : give news to Mr. Gérard, chief clerk at Fort Dauphin, to whom he belongs. There will be one portuguese as a reward." (Transl.) (46)These captives (slaves) from Madagascar were ethnically diverse, as is the case today. There were Blacks, Half-breeds, and Hindus (or Indians). The latter, bearing the name of Indians in the advertisements, led some to believe that they were Amerindians.

e) Ethiopia

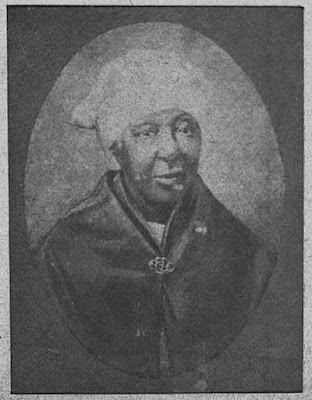

We cannot fail to mention this renowned freed captive (slave) from Ethiopia. Marthe Adélaïde Modeste Testas, nicknamed Modeste Testas or Pelagie, was born in 1765 in Adele (Adele Keke, in the region of Arari located on the Ethiopian-Somali border). She was the maternal grandmother of François-Denys Légitime, former interim president of Haiti (December 18, 1888 - August 22, 1889).

(Statue in Bordeaux of Modeste Testas, freed Dominguan captive (slave) from Ethiopia)

At birth, Modeste Testas was given the name of Oriol-Poci or Alpouci. As a teenager, she was kidnapped by a member of another ethnic group seeking revenge on her father who embarked on a pilgrimage. Sold into slavery by her captor, she first transited through Bordeaux in France. Then she landed in Port-au-Prince where she was bought by François Testas who made her his companion. She was then taken to Jérémie, in Southeastern Saint Domingue.

(François-Denys Légitime, 16th President of Haiti, grandson of Modeste Testas)

After being freed at the death of François Testas in July 1795, Modeste Testas or Pélagie paired up with Joseph Lespérance, who was also freed by the same master. They had several children, including Antoinette "Tinette" Lespérance, the mother of President Légitime. (47)

(Antoinette "Tinette" Lespérance, the mother of President Légitime, and daughter of Modeste Testas)

5.2- Presence of captives (slaves) from Southern "Africa"

Let's push further our argument that the presence in Saint Domingue of captives (slaves) not coming from Western or Central "Africa" is massively undervalued. Along "Africa's" Eastern Coast, we reach Southern "Africa", that is to say, South of the continent. The next country listed is Zimbabwe. Here was the site of an Empire that covered the continent's Southern expanse, from sea to sea. It's the Mutapa Empire, also called Great Zimbabwe or Monomotapa :

(The Monomotapa Empire)

Source

: Willem Janszoon Blaeu, 1635. "'Aethiopia inferior, vel exterior';

copperplate map from 'Theatrum orbis terrarum sive atlas novus'

Published in Amsterdam." ; URL :

http://libweb5.princeton.edu/visual_materials/maps/websites/africa/maps-southern/1635%20blaeu.jpg

This Empire was recognized for its remarkable conical brick constructions :

Source : Jan Derk, 1997. "Inside of the Great Enclosure which is part of the Great Zimbabwe ruins" ; URL : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shona_people#/media/File:Great-Zimbabwe-2.jpg

(Ruins of a Monomotapa site)

Sources : "Zimbabwe Closeup", 2008. ; URL : https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Empire_du_Monomotapa#/media/File:Great_Zimbabwe_Closeup.jpg

Colonist historian Moreau de Saint Méry identified captives (slaves) who were classified in Saint Domingue as "Monomotapa". (48) However, in the runaway ads, they were referred to, in reference to the Kingdom of Mutapa, as members of the Matapa, Atapa or Tapa nation :

"On the 20th, Jasmin, Matapa nation, unstamped, aged between 30 and 36 years, 5 feet 2 inches tall, claiming to belong to Mr. Bernard." (Transl.) (49)

In the colony, the captives (slaves) from this Kingdom were also called in reference to a spot in the Mutapa Kingdom that was Danangombe. In the advertisements, derivatives of Danangombe were multiple : Dagouamba, Daguamba, Dangouama, Dangoname, Dangoua, Dagouan, Danguan, Danguam, Dangonem, Bangouam, Dagouam, Dangoma, Dangouan, etc. :

"On the 24th, Charles, Dagouamba, stamped horseshoe shaped CHASTULE, refusing to say the name of his master." (Transl.) (50)

Among the Saint Domingue captives (slaves), there were also the Limba (or Linba) who came from Zimbabwe, South Africa and Malawi. However, it would be difficult to distinguish them from those belonging to the Limba ethnic group from Cameroon. And finally, the sacred Zulu Nation or Nanchon Zoulou from South Africa, has its place in the traditional Haitian ritual. An additional proof of the presence of captives (slaves) native of Southern "Africa" in Saint Domingue.

In short, this Yaya ethnic group could refer to the Kenyan traditionalist Munyo Yaya people as to another people that escapes us for the moment. This Yaya people listed in Saint Domingue could also have no connection with the nickname Gillot, the rebel leader of Trou du Nord. But anyway, the clues point generally to a non-islamic link to the name Yaya, in the Saint Domingue colony.

In short, this Yaya ethnic group could refer to the Kenyan traditionalist Munyo Yaya people as to another people that escapes us for the moment. This Yaya people listed in Saint Domingue could also have no connection with the nickname Gillot, the rebel leader of Trou du Nord. But anyway, the clues point generally to a non-islamic link to the name Yaya, in the Saint Domingue colony.

* Canga, the Congo name, should not be confused with the Canga Nation, which was the ethnicity of many fugitives or maroons in Saint Domingue :

"A Negro named Pierre-Louis, Canga nation, stamped on the two breasts DE BOYNES, about 25 to 27 years old, about 5 feet tall, of good build, with a round face, big lips, big grave voice, crippled at the thumb of his right hand, has been marooned since last October 18. The said Negro belongs to the estate of Boynes, called de Béon, in the plain of Cul-de-Sac." (Transl.) (51)This "Canga Nation", originally from the Windward Coast (present-day Ivory Coast), did not really constitute an ethnic group. It actually references the non-coastal village of Kanga Nianzè, located North of Abidjan, the capital of Côte d'Ivoire. It was a place where captives were brought from many corners of Côte d'Ivoire. The reason for this "storage" of captives lies in the place name : "Kanga", in the Baoulé language, means "slave", and "Gnianzé" means "water" in which a "purifying Bath of Forgetfulness" took place.

(Purifying Bath of Forgetfulness in Kanga Nianzè)

Source

: ©AFP/ISSOUF SANOGO. URL :

http://www.rfi.fr/emission/20170730-cote-ivoire-route-esclave-kanga-nianze-bain-purification

Thus, at Kanga Nianzè, before forcibly taking the captives "Kanga" into the slave ships, they were led to the Bodo River where an officiant administered a bath to make them forget their identity. (52) It is reminiscent of "The Tree of Forgetfulness" in Ouidah, in the former slave-holding Kingdom of Dahomey (present-day Benin) :

(Where once stood the Tree of Forgetfulness, in Ouidah)

Source

: Barada-nikto. "Arbre de l'oubli à Ouidah, Bénin : Surmontée d'une

représentation de Mami Wata." URL :

https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fichier:Arbre_de_l_oubli_ouidah_benin.jpg

Around this tree, they forced the captives to make several turns to forget their identity before boarding the slave ships :

Around this tree, they forced the captives to make several turns to forget their identity before boarding the slave ships :

"OUIDAH 92

L'ARBRE DE L'OUBLI

En ce lieu se trouvait l'arbre de l'oubli.

Les esclaves mâles devaient

tourner autour de lui neuf fois,

les femmes sept fois.

Ces tours étant accomplis les esclaves

étaient censés devenir amnésiques.

Ils oubliaient complètement leur passé

leurs origines et leur identité culturelle

pour devenir des êtres sans aucune volonté

de réagir ou de se rebeller."

En ce lieu se trouvait l'arbre de l'oubli.

Les esclaves mâles devaient

tourner autour de lui neuf fois,

les femmes sept fois.

Ces tours étant accomplis les esclaves

étaient censés devenir amnésiques.

Ils oubliaient complètement leur passé

leurs origines et leur identité culturelle

pour devenir des êtres sans aucune volonté

de réagir ou de se rebeller."

Translation :

"OUIDAH 92

THE TREE OF FORGETFULNESS

In this place stood the tree of forgetfulness.

Male slaves had to

turn around it nine times,

women seven times.

These turns being performed slaves

were supposed to become amnesic.

They completely forgot about their past

their origins and their cultural identity

to become beings without any will

to react nor to rebel."

Source : Ji-Elle. "Ouidah (Bénin) : Arbre de l'Oubli." URL : https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/8/8f/Ouidah-Arbre_de_l%27Oubli_%282%29.jpg

And afterwards, the captives were brought to the Tree of Return :

(Tree of Return, in Benin)

Source

: Ji-Elle. "Ouidah (Bénin) : l'Arbre du Retour". URL :

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Arbre_du_Retour,_Ouidah#/media/File:Ouidah-Arbre_du_Retour_(1).jpg

Around this Tree of Return, they performed 3 turns, so that at their death, their souls could return to their homeland :

"OUIDAH 92

L'ARBRE DU RETOUR

En Sortant de Zomaï

Les esclaves devaient faire

trois fois le tour de cet arbre.

Cette cérémonie signifiait que le souffle

des esclaves reviendrait ici

après leur mort.

Le retour dont il est question ici

n'est donc pas physique mais mystique."

L'ARBRE DU RETOUR

En Sortant de Zomaï

Les esclaves devaient faire

trois fois le tour de cet arbre.

Cette cérémonie signifiait que le souffle

des esclaves reviendrait ici

après leur mort.

Le retour dont il est question ici

n'est donc pas physique mais mystique."

Translation :

"OUIDAH 92

THE TREE OF RETURN

Leaving Zomaï

Slaves had to make

three turns around this tree.

This ceremony meant that the slaves'

breath would return here

after their death.

The return we are talking about here

is not physical but mystical."

Source : Ji-Elle. "Ouidah (Bénin) : l'Arbre du Retour (3)". URL : https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Arbre_du_Retour,_Ouidah#/media/File:Ouidah-Arbre_du_Retour_(3).jpg

So the genocidal principle was similar, that it was to spiritually drown the captive's memory in the Bodo River in Côte d'Ivoire's Kanga Nianzè village. Or that it was to spiritually stun the captive via the turns around the Tree of Forgetfulness, in Ouidah, Benin. Obviously, in these two cases, it did not work for captives (slaves) deported to Saint Domingue (now Haiti). Because the Haitian, formerly "Kanga", despite having taken the Bath of Forgetfulness in Kanga Nianzè, still remembers and venerates Cap Lahou, their boarding port in Ivory Coast, as the Divinity and sacred Kaplawou Nation. Likewise, via the Divinity Èzili Freda Dawomen, the Haitian still remembers and venerates the city of Ouidah and the Foëda tribe associated with it, despite having performed the turns around the Tree of Forgetfulness. However, the traditionalist Haitians agree that upon their deaths, they will return to Nan Ginen, that is, to their homeland, as their ancestors had sealed it through the turns around the Tree of Return.

** http://african-origins.org/african-data/detail/5324 ; http://african-origins.org/african-data/detail/29366 ; http://african-origins.org/african-data/detail/35100 ; http://african-origins.org/african-data/detail/180656

*** In addition to the East-"African" Kamba or Akamba Nation, known as Camba or Macamba in Saint Domingue, there was also the Chamba Nation known in that colony as Chambar, Chambat, or Samba :

"On the 8th of the current [month], Samedi of the Chamba nation, stamped DL RIVIERE, and below AU FORT-D., Claiming to belong to the heir of the estate of the late Mr. D. Riviere, merchant at Fort Dauphin." (Transl.) (53)This latter nation, however, comes from Western "Africa" (Central-Eastern Nigeria) and Central "Africa" (North-Western Cameroon). The Chamba, which nowadays is sometimes called Camba, were traditionalists during the time of the Saint Domingue colony. They did not cease to resist islam up until the 20th christian century. (54) Moreover, in traditionalist Chambaland, the clairvoyants are called "ne tug an", that is to say "people with eyes", (55) a concept that persists in the traditional Haitian ritual.

**** Not to be confused with the much larger Ibo nation in Saint Domingue, that came from present-day Nigeria.

Notes

(1) Moreau de Saint Méry. Description topographique, physique, civile, politique..., Tome 1. Philadelphie, 1797. p. 176.

(2) Sylviane Diouf. Servants of Allah: African Muslims Enslaved in the Americas. New York, 1998. p.150.

(3) Colonel Malenfant. Des colonies et particulièrement de celle de Saint-Domingue mémoire historique et politique. Paris, 1814. p. 215.

(4-5) M.L.E. Moreau de Saint Méry. Description topographique, physique, civile, politique..., Tome 1. Philadelphie, 1797. pp.154, 175-176.

(6-7) M.L.E. Moreau de Saint Méry. Loix et constitutions des colonies françaises de l'Amérique Sous le Vent. Tome 3. Paris, 1795. pp.399, 402-403.

(8) M.L.E. Moreau de Saint Méry. Description topographique..., Tome 1. Op. Cit. p.176.

(9) M.L.E. Moreau de Saint Méry. Loix et constitutions... Tome 5. Paris, 1795. p.800.

(10) Les Affiches Américaines du Mardi 12 janvier 1779. Parution no.2. p.0.

(11) Moreau de Saint Méry. Loix et constitutions... Tome 3. Op. Cit. pp.167-169.

(12) Les Affiches Américaines du Mardi 27 novembre 1781. Parution no.48. p.465.

(13) Les Affiches Américaines du Mercredi 25 janvier 1786. Parution no.4. p.40.

(14) Les Affiches Américaines du Mercredi 24 mai 1786. Parution no.21. p.270.

(15) Hervé du Halgouet. Inventaire d'une habitation à Saint-Domingue. Paris, 1933. p.249.

(16) Affiches américaines du vendredi 19 juillet 1793. Parution no.9. pp.39-40, 43-44.

(17) P. Roux. Almanach royal d'Hayti. Cap-Henry, 1816. p.91.

(18) Feuille du commerce, petites affiches et annonces du Port-au-Prince No.14, du 6 avril 1851, p.3.

(19) Claude Planson. Le vaudou. Paris, 1974. pp.257-258.

(20) Prophète Joseph. Dictionnaire Haïtien-Français. Montréal, 2003. p.115.

(21) M.L.E. Moreau de St. Méry. Description topographique..., Tome 1. Op. Cit. pp.46, 50.

(22) Lovejoy Paul E. "Islam, slavery, and political transformation in West Africa : constraints on the trans-Atlantic slave trade". In: Outre-mers, tome 89, n°336-337, 2e semestre 2002. traites et esclavages : vieux problèmes, nouvelles perspectives ? pp. 247- 282.

(23) Michael Garfield Smith. Government in Zazzau: 1800-1950. London, 1960. p.6.

(24) Christoph Henning, Klaus E. Müller, Ute Ritz-Müller. Afrique-La magie dans l’âme : rites, charmes et sorcellerie. Könemann, 2000. p.284.

(25-26) Benard Nantet. Dictionnaire d'histoire et civilisations africaines. Paris, 1999. pp.134, 43.

(27) Beauvais Lespinasse. "Danses et chants nationaux d'Haïti. III : Carabinier" In : Le Républicain : Recueil scientifique et littéraire du 1er janvier 1837. No.10. pp.5-8.

(28) M.L.E. Moreau de Saint Méry. Description topographique... Tome 1. Op. Cit. p.28.

(29) Jean-Baptiste-Léonard Durand. Voyage au Sénégal ou Mémoires historiques. Paris, 1802. pp.99-100.

(30) Dictionnaire (Lexique) Kikongo-Français. [online] URL : https://www.abibitumikasa.com/forums/showthread.php/48048-Dictionnaire-%28Lexique%29-Kikongo-Fran%C3%A7ais?s=62feb6a36f48a420e6669a1af4115647

(31) Prophète Joseph. Dictionnaire Haïtien-Français. Op. Cit. p.115.

(32-33) Ignace Nau. "Un Épisode de la Révolution" In : Le Républicain, Recueil Scientifique et Littéraire. No.9, 15 janvier 1836. pp.2-7.

(34) Les Affiches Américaines du Mercredi 9 août 1786. Parution no.32. p.409.

(35) "The Rev. R. M. Ormerod's journey on the Tana River". In : The Geographical Journal, volume, No.3. September 1896. pp-283-293. (p.286.)

(36-37) Les Affiches Américaines du mardi 13 avril 1779. Parution no.15. p.0.

(38) Les Affiches Américaines du jeudi 11 février 1790. Parution no.12. p.76.

(39) Les Affiches Américains du mercredi 26 août 1789. Parution no.69. p.463.

(40) Les Affiches Américaines du mercredi 21 juin 1769. Parution no.25. p.194.

(41) Les Affiches Américaines du jeudi 19 juillet 1787, Parution no.57. p.363.

(42) M.L.E. Moreau de Saint Méry. Description topographique..., Tome 1. Op. Cit. p. 34.

(43) James G. Leyburn. "The making of a Black nation". In : Studies in the science of society. 1937. pp.377-394. (p.386)

(44) Les Affiches Américaines du jeudi 22 avril 1790. Parution no.32. p.219.

(45) Voegeli Juste-Constan. "La Musique dans le carnaval haïtien : Aspects urbains et ruraux." (Thèse) Montréal, 1994. pp.126-128.

(46) Les Affiches Américaines du samedi 27 décembre 1788. Parution no.52. p.1048.

(47) Andre F. Chevallier. "Président Légitime" In : Aya Bombé! Revue mensuelle. No.8. Port-au-Prince, Mai 1947. pp.8-9.

(48) M.L.E. Moreau de Saint Méry. Description topographique..., Tome 1. Op. Cit. p.34.

(49) Les Affiches Américaines du mercredi 26 juin 1776. Parution no.26. p.302.

(50) Les Affiches Américaines du samedi 29 juillet 1786. Parution no.30. p.389.

(51) Les Affiches Américaines du mardi 29 décembre 1778. Parution no.51. p.0.

(52) See "Côte d'Ivoire: émotion et souvenir autour de l'esclavage". URL : https://www.lexpress.fr/actualites/1/styles/cote-d-ivoire-emotion-et-souvenir-autour-de-l-esclavage_1925314.html ; Retrieved December 20, 2018. ; Listen to : Élikia M'Bokolo. "Route de l'esclave : enfin, la Côte d'Ivoire!", Podcast : "Mémoire d'un continent" du dimanche 30 juillet 2017. URL : http://www.rfi.fr/emission/20170730-cote-ivoire-route-esclave-kanga-nianze-bain-purification

(53) Les Affiches Américaines du samedi 13 janvier 1787. Parution no.2. p.661.

(54-55) Richard Fardon. Between God, the Dead and the Wild : Chamba Interpretations of Religion and Ritual. Edinburgh, 1990. pp.190, 36-37.

(1) Moreau de Saint Méry. Description topographique, physique, civile, politique..., Tome 1. Philadelphie, 1797. p. 176.

(2) Sylviane Diouf. Servants of Allah: African Muslims Enslaved in the Americas. New York, 1998. p.150.

(3) Colonel Malenfant. Des colonies et particulièrement de celle de Saint-Domingue mémoire historique et politique. Paris, 1814. p. 215.

(4-5) M.L.E. Moreau de Saint Méry. Description topographique, physique, civile, politique..., Tome 1. Philadelphie, 1797. pp.154, 175-176.

(6-7) M.L.E. Moreau de Saint Méry. Loix et constitutions des colonies françaises de l'Amérique Sous le Vent. Tome 3. Paris, 1795. pp.399, 402-403.

(8) M.L.E. Moreau de Saint Méry. Description topographique..., Tome 1. Op. Cit. p.176.

(9) M.L.E. Moreau de Saint Méry. Loix et constitutions... Tome 5. Paris, 1795. p.800.

(10) Les Affiches Américaines du Mardi 12 janvier 1779. Parution no.2. p.0.

(11) Moreau de Saint Méry. Loix et constitutions... Tome 3. Op. Cit. pp.167-169.

(12) Les Affiches Américaines du Mardi 27 novembre 1781. Parution no.48. p.465.

(13) Les Affiches Américaines du Mercredi 25 janvier 1786. Parution no.4. p.40.

(14) Les Affiches Américaines du Mercredi 24 mai 1786. Parution no.21. p.270.

(15) Hervé du Halgouet. Inventaire d'une habitation à Saint-Domingue. Paris, 1933. p.249.

(16) Affiches américaines du vendredi 19 juillet 1793. Parution no.9. pp.39-40, 43-44.

(17) P. Roux. Almanach royal d'Hayti. Cap-Henry, 1816. p.91.

(18) Feuille du commerce, petites affiches et annonces du Port-au-Prince No.14, du 6 avril 1851, p.3.

(19) Claude Planson. Le vaudou. Paris, 1974. pp.257-258.

(20) Prophète Joseph. Dictionnaire Haïtien-Français. Montréal, 2003. p.115.

(21) M.L.E. Moreau de St. Méry. Description topographique..., Tome 1. Op. Cit. pp.46, 50.

(22) Lovejoy Paul E. "Islam, slavery, and political transformation in West Africa : constraints on the trans-Atlantic slave trade". In: Outre-mers, tome 89, n°336-337, 2e semestre 2002. traites et esclavages : vieux problèmes, nouvelles perspectives ? pp. 247- 282.

(23) Michael Garfield Smith. Government in Zazzau: 1800-1950. London, 1960. p.6.

(24) Christoph Henning, Klaus E. Müller, Ute Ritz-Müller. Afrique-La magie dans l’âme : rites, charmes et sorcellerie. Könemann, 2000. p.284.

(25-26) Benard Nantet. Dictionnaire d'histoire et civilisations africaines. Paris, 1999. pp.134, 43.

(27) Beauvais Lespinasse. "Danses et chants nationaux d'Haïti. III : Carabinier" In : Le Républicain : Recueil scientifique et littéraire du 1er janvier 1837. No.10. pp.5-8.

(28) M.L.E. Moreau de Saint Méry. Description topographique... Tome 1. Op. Cit. p.28.

(29) Jean-Baptiste-Léonard Durand. Voyage au Sénégal ou Mémoires historiques. Paris, 1802. pp.99-100.

(30) Dictionnaire (Lexique) Kikongo-Français. [online] URL : https://www.abibitumikasa.com/forums/showthread.php/48048-Dictionnaire-%28Lexique%29-Kikongo-Fran%C3%A7ais?s=62feb6a36f48a420e6669a1af4115647